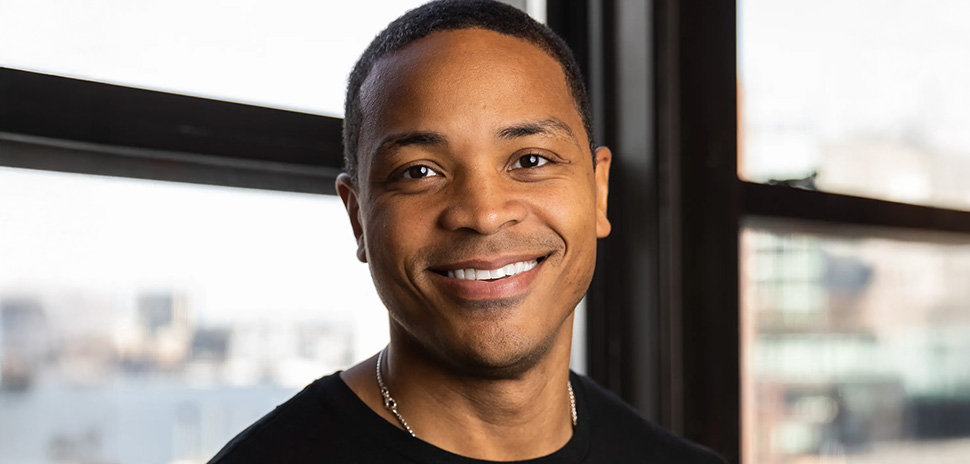

After a sudden move from its DeSoto farm, Farmers Assisting Returning Veterans has relocated its operation to 200 acres of bottomland in Seogoville.

The new land off Bilindsay Road east of Interstate 45 is susceptible to flooding and has a destroyed irrigation system, but that hasn’t deterred executive director and co-founder Steve Smith.

“Some people look at it as intimidating,” Smith said. “I look at it as potential.”

![Steve Smith, left, and the team at F.A.R.M. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Talking-Crop-8010.jpg)

Since 2012, F.A.R.M. has assisted more than 250 veterans and raised around $400,000 to aid veterans with their reintegration process into society. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

Since 2012, F.A.R.M. has assisted more than 250 veterans and raised around $400,000 to aid veterans with their reintegration process into society. Through internships and workshops, participants farm as a therapeutic way to readapt to civilian life.

“Some people look at it as intimidating. I look at it as potential.”

STEVE SMITH

But with this move, came devastating loss — $300,000 worth of produce, $10,000 in pigs, and other animals. This has not slowed the organization’s mission though, but rather given it more motivation to adjust and expand.

“We’re just starting over and I’m rolling with the punches,” Smith said. “But [there are] so many good things happening, I don’t like dwelling on all those bad things.”

F.A.R.M. RESTRUCTURES VETERAN PROGRAMS

Previously, F.A.R.M. focused on placing participants in an intense six-month internship to immerse them within the world of farming. To accommodate veterans who may be unsure or unwilling to dedicate themselves to an internship, Smith said the nonprofit will offer a six-week F.A.R.M camp to match potential farmers with experienced mentors to get a feel for the work.

![Pigs at F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Pig-Crop-7991.jpg)

Pigs at F.A.R.M. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

“They would rotate out to see what chickens are like, and what pigs are like, and what rabbits are like, and what vegetable farming is like, and over that six-week period they get their hands dirty and figure it all out,” Smith said.

Smith has received other land offers, some at no cost. By acquiring multiple sites, the nonprofit plans to use the already acquired land as an incubator for new farmers in the program, and other locations for farmers to launch their own farming operations.

Farming operations manager Jason Corbin, who has been with the nonprofit for the past year and a half, plans to be a mentor for the program. He is starting his own farm on the land, with chickens, rabbits, rare bird breeds, and vegetables.

![Steve Smith [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Group-Listening-Crop-8007.jpg)

[Photo: Chase Mardis]

“We give them however much land they need and we check out their business plans, lead them in the right direction and say, ‘Go get it!’”Corbin said.

TINY HOME VILLAGE TO HOUSE PARTICIPANTS

Before these programs begin, housing must be built for participants to stay in during their time with F.A.R.M. Since the land is on a flood plain, insurance to build a house is impossible to get. The solution: tiny homes with the ability to move when conditions become too dangerous.

Smith plans on 12, 160-square-foot houses that will take four to six weeks to build. At that pace, the village will be complete and running within a year.

“I always go through and teach them what I know and talk to them and sometimes I just listen to them, that’s all they need.”

JASON CORBIN

There will be a central dining facility for participants to eat meals together that also will function as a classroom for workshops and alternative therapies, such as yoga.

Funding for these structures is an issue, and Smith is seeking donations and grants for construction costs. He predicts each tiny home will cost about $32,000. He said the previous money F.A.R.M. generated has been completely used up.

“We don’t have a single dollar to show for it left,” Smith said. “It all went into those programs and services and now we’re back to where we have an empty bank account and not able to do much.”

THE FUTURE OF F.A.R.M.

Although in a transition period, the mission of F.A.R.M. remains the same. Through this new program and village of tiny homes, F.A.R.M.’s main focus continues to be helping veterans.

Justin Phillips, one of F.A.R.M.’s current participants, came directly to the program from an in-patient stay at a psychiatric hospital, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injuries.

Growing up, Phillips raised chickens and hated it. Little did he know, similar experiences would aid his recovery from his military service.

“… we’re just one big family.”

JUSTIN PHILLIPS

“As I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown to love it,” Phillips said. “It’s something that I will do for the rest of my life.”

Learning independently and as a community, Phillips has enjoyed the program and plans to stick with it.

“We’re here for each other, too. It’s not like he’s on his own and I’m on my own, it’s we’re on our own, but we’re here together and everybody else. We’re just one big family,” Phillips said.

He’s planning to be a mentor for F.A.R.M. camp, helping others find the comfort and therapy they seek.

Corbin feels similarly that his mentorship in farming can change a veteran’s attitude and give them a sense of purpose.

“We just can’t wait to get back to farming again.”

HYIAT EL-JUNDI

“I’ve had several volunteers come through, and I always go through and teach them what I know and talk to them and sometimes I just listen to them, that’s all they need,” Corbin said.

Through their trials, the leaders of F.A.R.M. are ready to just get their hands back in the dirt.

“We just can’t wait to get back to farming again,” said development director Hyiat El-Jundi.

PHOTO GALLERY

![F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Wheelbarrow-Crop-7995.jpg)

F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Compost vegetables at F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Compost-vegetables-Crop-7994.jpg)

Compost vegetables at F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Pigs at F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Side-shot-of-small-greenhouse-Crop-7993.jpg)

Side shot of small greenhouse at F.A.R.M. in Seagoville. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Steve Smith [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Steve-Smith-Talking-Crop-8005.jpg)

Steve Smith [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Steve Smith, left, and the team at F.A.R.M. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Large-tent-Crop-8015.jpg)

Large greenhouse tent [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Steve Smith, left. [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Steve-Smith-Listening-Crop-8008.jpg)

Steve Smith, left. [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Small greenhouse [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Small-Greenhouse-No-Crop-8016.jpg)

Small greenhouse [Photo: Chase Mardis]

![Steve Smith [Photo: Chase Mardis]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Steve-Smith-Portrait-Crop-8019.jpg)