URBAN FARMING HELPS VETERANS TRANSITION INTO CIVILIAN LIFE

It’s no secret that it can be hard for returning veterans to assimilate into civilian society. When they enter basic training, recruits are broken down, taught to think differently. They shed their civilian skin and become soldiers. Reversing that transformation can be an isolating, depressing, and difficult experience.

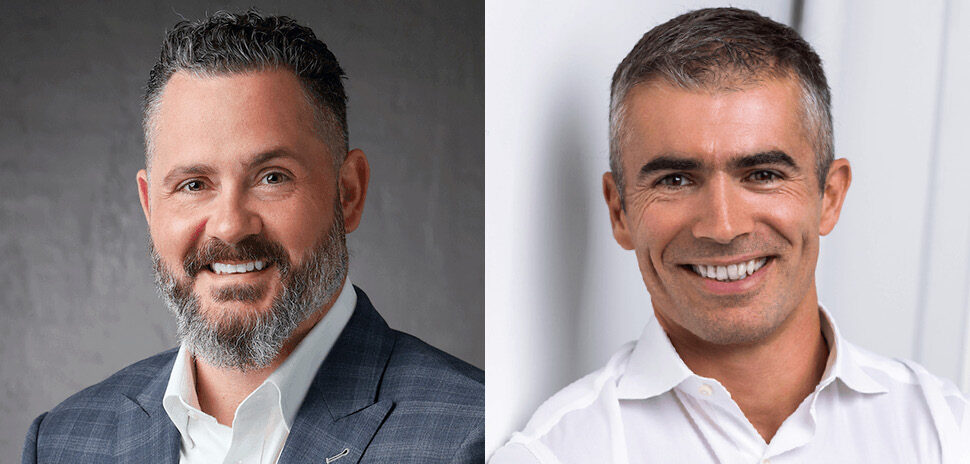

It’s a struggle that Steve Smith and James Jeffers know well. The two were stationed at Fort Hood together and served overseas at different points in their military careers. When they came back after their service, they found that integrating back into society was a challenge.

In an effort to amend their eating habits and engage their minds and bodies, they took up organic urban farming. They focused on a sustainable, “closed-loop” system, and soon found that the fruits of their labor—both the psychological benefits of the work, and the green, leafy goodness that sprouted from the soil—were more than they could have hoped.

In 2012, the endeavor expanded into a farming business called Eat the Yard, which sells produce at the Dallas Farmers Market and to citizens, restaurants, and small grocers.

VETERAN SUICIDE LEADS TO NONPROFIT’S ORIGIN

According to the Department of Veteran Affairs’ 2012 Suicide Data Report, approximately 22 military veterans committed suicide every day in 2010. Multiplied out, that’s more than 8,000 annually.

Farming helped Smith and Jeffers cope, but as suicide claimed people they’d served with, they knew they needed to find a way to help those still struggling. In an effort to share their special kind of “dirt therapy,” the two created Farmers Assisting Returning Military, or F.A.R.M., a nonprofit outreach program based out of a 17-acre farm in DeSoto.

They called up Orlando Garcia, a friend who had recently retired from the military after more than 23 years of service, and told him they needed his help. In a flash, Garcia turned in his notice for his job at Fort Hood and soon moved to Dallas.

“It starts to boil over: depression kicks in, anger kicks in, and that’s when suicidal ideation sets in.”

-Orlando Garcia

“At the time, we’d just lost another brother to suicide, and it couldn’t wait,” Garcia said. “Veterans are coming out of the military with three to seven to eight tours of duty under their belts—and they find themselves isolated. It starts to boil over: depression kicks in, anger kicks in, and that’s when suicidal ideation sets in.”

NURTURING VETERANS’ MIND, BODY, SOUL

F.A.R.M. is about providing veterans with support, with a purpose, and with a sense of community. The nonprofit has three distinct components, the foremost of which is the agricultural therapy. This exposes veterans to the therapeutic value of working the land (through organic farming, composting, hydroponics, aquaponics, and farm animals). Through “dirt therapy,” veterans are taught valuable skills and given a sense of purpose.

F.A.R.M. also provides a medical treatment component, which helps ensure that veterans are getting the care they need from trained professionals, whether in the realm of trauma resolution or in transitioning away from prescriptions and toward holistic health.

And lastly, F.A.R.M.’s recreational component connects veterans with a community and organizes a host of activities, including camping, fishing, climbing, and off-roading. This is particularly beneficial in helping to mend the gap between veterans and civilians, and in aiding with veterans’ transition.

But first and foremost, according to Garcia, is the sense of support the organization provides—an antidote for isolation.

“We’re not giving them money; we’re giving them seeds to plant.”

-Orlando Garcia

“Even if I just go out there with my brothers and help them fill a basket of arugula or kale—the point is, I’m talking to them,” he said. “The farming is a side-point; we could be basket-weaving. But if we’re going to do something, what’s better than teaching veterans about healthy and sustainable living? We’re not giving them money; we’re giving them seeds to plant.”

In the future, F.A.R.M. hopes to be able to house and train 20 veterans in agricultural practices at a time, Garcia said. The organization also plans to open Urban Farm Park, a community educational facility located close to the Dallas Farmer’s Market that will host programs and classes.

“Veterans deserve care and sustainable skills,” Garcia said. “Veterans have given us so much—don’t make them an afterthought. I’m tired of losing my brothers to suicide.”

For a daily dose of what’s new, now, and next in Dallas-Fort Worth innovation, subscribe to our Dallas Innovates e-newsletter.