Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas have discovered that could lead to an effective treatment for acute alcohol intoxications.

The researchers reported in a new study that a shot of a liver-produced hormone called FGF21 sobered up mice that had passed out from alcohol. It allowed them to regain consciousness and coordination much faster than those that didn’t receive the treatment, UT Southwestern said.

Acute alcohol intoxication is responsible for about 1 million emergency room visits in the U.S. each year, UT Southwestern said.

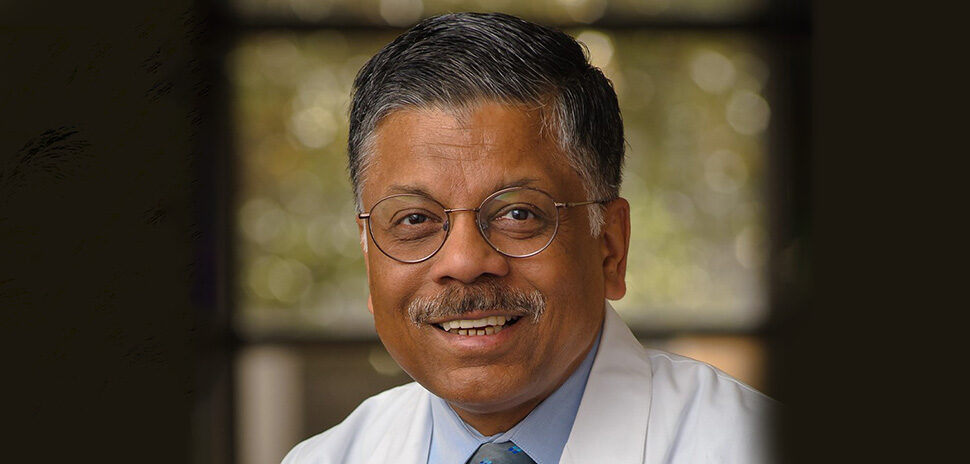

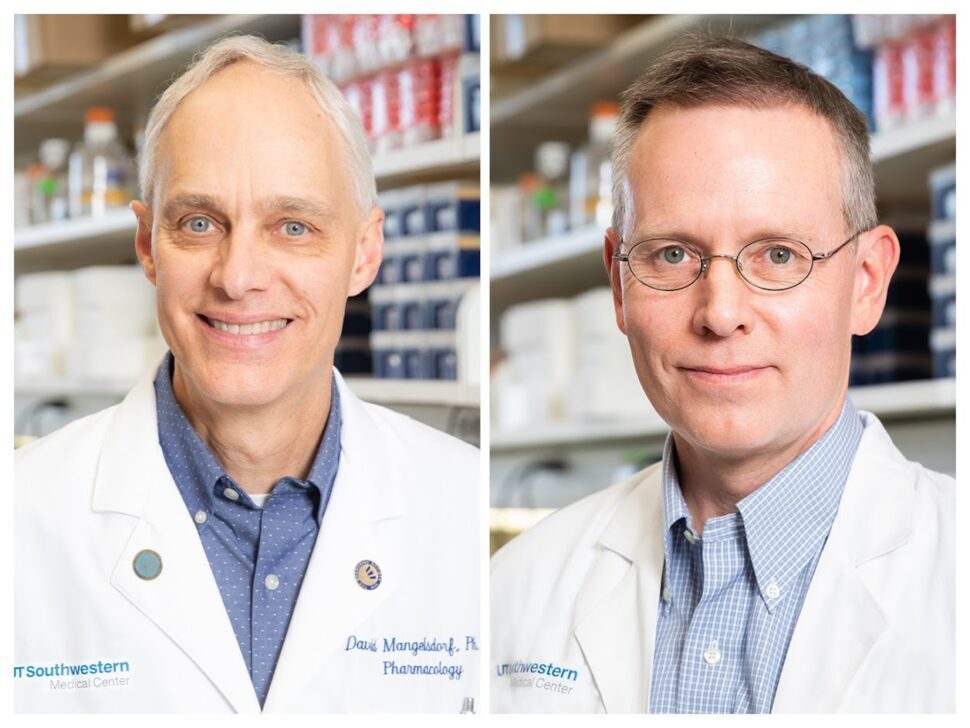

“Humans have long searched for agents that could reverse drunkenness, and now we have discovered something to achieve this effect that’s been in our bodies the whole time,” David Mangelsdorf, Ph.D., chair and professor of Pharmacology, Professor of Biochemistry at UTSW, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, said in a statement.

Quest to speed up sobering process

UTSW’s Dr. David Mangelsdorf (left) and Dr. Steven Kliewer [Courtesy photo]

Mangelsdorf co-led the study with his longtime collaborator, Steven Kliewer, Ph.D., professor of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, and Mihwa Choi, Ph.D., an instructor of Pharmacology.

Kliewer said that for thousands of years, humans have attempted to speed up the sobering process after drinking too much alcohol.

He said, for example, the ancient Greeks believed that amethyst could protect people from drunkenness, so they drank out of chalices carved from the semiprecious stone.

There is no treatment for alcohol intoxication, however. Beyond removing undigested alcohol by pumping the stomach and preventing people from aspirating their own vomit, sobering up takes time, Mangelsdorf said.

The effects of FGF21

In recent years, Mangelsdorf, Kliewer, and their colleagues discovered that FGF21 discouraged alcohol drinking in sober mice and encouraged water drinking to prevent dehydration in intoxicated mice.

UT Southwestern said that other researchers found that this hormone appears to protect against alcohol-related liver injury. UTSW scientists found that mice genetically altered to delete the gene that produces FGF21 took far longer than unaltered mice to become sober after acute alcohol poisoning.

As part of this latest study, the researchers delivered enough alcohol to mice to render them unconscious, mimicking a binge drinking session, UT Southwestern said.

Scientists then injected some of the animals with FGF21. While those that didn’t receive this agent took about three hours to regain consciousness and stand upright, those that received FGF21 accomplished it in half the time.

When scientists delivered smaller amounts of alcohol more akin to typical human drinking – enough to significantly affect the animals’ coordination – the mice that got FGF21 injections also regained their coordination much faster than those that didn’t receive the hormone.

UTSW said that further investigations showed that FGF21 acts on noradrenergic neurons, a type of nerve cell in the brain that promotes wakefulness. The hormone didn’t affect alcohol metabolism as both treated and untreated mice showed the same blood alcohol concentrations.

Kleiner said that FGF21 appears to specifically affect intoxication from alcohol. Animals that received other types of sedatives did not become alert any faster than usual when given this hormone.

Potential treatment for acute intoxication

Mangelsdorf said that FGF21 already has been explored in clinical trials involving diabetes, weight loss, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and has shown a good safety profile.

He said that eventually FGF21 could be developed into a drug that could be delivered to patients in hospital emergency rooms, college campuses, or elsewhere akin to the way Narcan is used to treat opiate overdoses, potentially saving countless lives.

“We don’t want to send the signal that it’s OK to get drunk because a drug can undo it,” Kliewer said. “But FGF21 may eventually be able to prevent some negative consequences for people incapacitated from alcohol.”

Other UTSW researchers who contributed to this study are Wei Fan, Abhijit Bugde, Laurent Gautron, Kevin Vale, Robert E. Hammer, and Yuan Zhang.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Robert A. Welch Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.

![Southwestern Medical Foundation President and CEO Kathleen Gibson has joined the board of nonprofit LaunchBio. [Image: Southwestern Medical Foundation; istockphoto]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Kathleen-Gibson-LaunchBio-board-970x464.jpg)