Sometimes research that scientists have been conducting for years zooms to the forefront because of world events. That’s what researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center are finding—together with international collaborators, they have discovered a genetic protein in the human immune system that won’t allow the coronavirus to trigger an infection.

For the experiments, Swiss collaborators obtained a sample of the virus that came from a patient, and a mouse model was developed at UT Southwestern.

The discovery could be an important step in finding treatments for the illness that has killed about 4,000 people to-date.

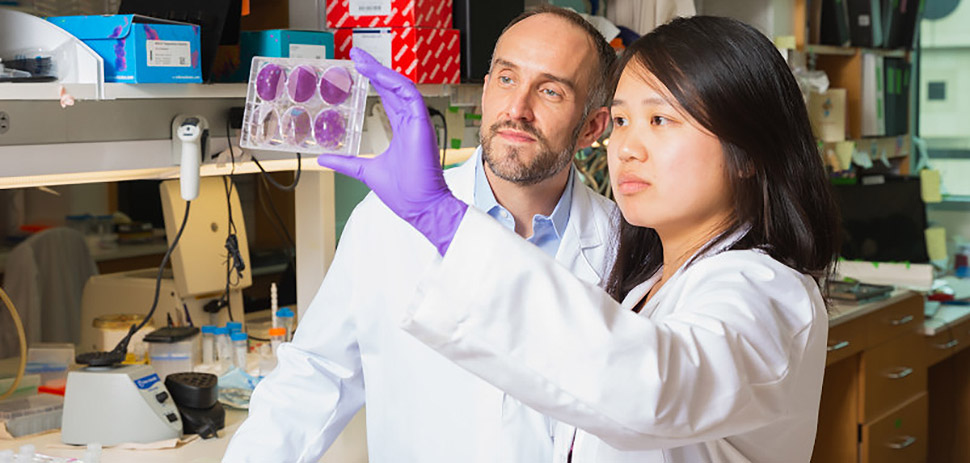

John Schoggins, associate professor of microbiology at UT Southwestern Medical Center, and Katrina Mar, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Schoggins lab at UTSW and co-lead author of the study, partnered with scientists in Switzerland and New York for the experimentation. The research team looked at the impact of the LY6E protein on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory (MERS) coronavirus, and the latest coronavirus, COVID-19.

In all three cases, the LY6E genetic protein inhibited the viruses’ ability to initiate infection.

“Because LY6E is a naturally occurring protein in humans, we hope this knowledge may help in the development of therapies that might one day be used to treat coronavirus infections,” Schoggins, PhD, said.

Like many scientific discoveries, this one was a byproduct of another study.

Before coming to UT Southwestern, Schoggins worked as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Charles M. Rice, PhD, at The Rockefeller University in New York. Schoggins was screening for antiviral genes and found that the LY6E genetic protein made the virus that causes influenza much more infectious.

In 2017, Stephanie Pfaender, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher from the University of Bern lab of Volker Thiel, PhD, one of the world’s leading experts on coronavirus, visited the Rice lab to use Schoggins’ screening technology to discover the effects of certain genetic proteins on the coronavirus.

Those findings showed that the same LY6E protein that made the flu more infectious had the opposite effect on the coronavirus. It potently inhibited corona.

UT Southwestern researchers, working in partnership with the Thiel and Rice labs, developed a mouse model to study the role of LY6E (called Ly6e in mice) in viruses, using a nonlethal form of coronavirus. The team had been working on coronavirus research for almost two years before the current outbreak.

To look at the respiratory diseases, they used primate kidney cells to determine that LY6E impairs the ability of the SARS and MERS coronaviruses to fuse with host cells, which means an infection is never triggered.

Earlier this year, Thiel got a sample of human COVID-19 and determined that LY6E also inhibited infection with the recent strain.

Meanwhile, in Dallas, Mar found that in the UTSW mouse model, Ly6e was critical in protecting immune cells from coronavirus infection. If Ly6e was lacking, the immune system had a much harder time fighting off the disease, because cells were more susceptible to infection.

However, it’s important to know that the mouse coronavirus differs from the current virus spreading across the globe. The coronavirus studied in mice affected the liver, causing hepatitis, and usually is not lethal. But, for mice without Ly6e, it was deadly.

“In spite of those differences, it’s widely accepted as a model for understanding basic concepts of coronavirus replication and immune responses in a living animal,” Schoggins said in a statement. “Our study brings new insight into how critical these antiviral genes are for controlling viral infection and mounting proper immune responses against the virus. Because LY6E is a naturally occurring protein in humans, we hope this knowledge may help in the development of therapies that might one day be used to treat coronavirus infections.”

In their study, which is still awaiting peer review, the researchers concluded that therapies mimicking the LY6E protein could provide a key defense against coronavirus. Similar antiviral fusion inhibitors have been successfully used for HIV-1.

And, in light of International Women’s Day, it’s notable that both lead authors of the study are women.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.