“At any given moment, 13 million people in the United States have cancer. For each of those 13 million, there are family members who are wondering: Is this cancer part of a pattern? Does cancer run in my family? Am I at risk?”

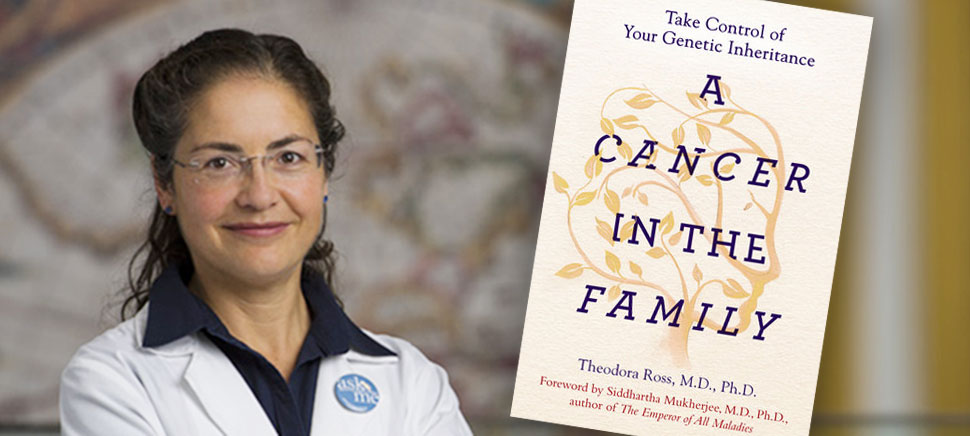

The potent statistics that give rise to difficult questions open Dr. Theodora Ross’ recently released book “A Cancer in the Family: Take Control of Your Genetic Inheritance.”

“The major motivation was to write a book that was useful, educational, and a good read for people interested in cancer and genetics,” says Ross, who directs UT Southwestern Medical Center’s Cancer Genetics Program. “To show the upside of knowing your genetic inheritance was a huge motivator.”

UT Southwestern’s Cancer Genetics Program sees more than 3,000 patients every year.

“Dr. Ross’ work with the physicians and genetic counselors in the Cancer Genetics Clinic help patients assess their risk for many types of cancer, including breast, ovarian, colon, endocrine, and pancreatic cancers,” says Dr. James K.V. Willson, associate dean of oncology programs at UT Southwestern. “In addition, she has spearheaded important scientific investigations into how cells transform from normal cells to cancer cells, and how some cancer cells are able to withstand specifically targeted cancer drugs.”

For patients who already have cancer, Ross and her team help identify the best course of action, such as which chemotherapy to take or whether investigational medicine may be an option.

“We’re cancer gene hunters,” Ross says.

Ross also gives readers a spirit of compassion and hope by sharing her own journey with inherited cancer.

“We’re cancer gene hunters,” Ross says.

“A Cancer in the Family” was released on February 2. Physician and oncologist Siddartha Mukherjee authored the book’s foreword. Mukherjee previously wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Emperor of All Maladies,” which tells the history of cancer treatment and research.

“The major point that I took from writing [‘A Cancer in the Family‘] is that when it comes to cancer and genetics, openness is a virtue,” Ross says.

Cancer Genetics: Ross’ Life Passion

Dr. Ross began her journey toward the field of cancer genetics while she was training as an M.D. and Ph.D student at Washington University in St. Louis. It was during that time the relatively new field to gain traction.

“Prior to that, there were a few pioneers—Lynch, King, Li and Fraumeni—who toiled away researching families that had cancer syndromes, but no associated gene mutations,” Ross says.

Then in 1994, BRCA1 gene was discovered, followed by the BRCA2 gene in 1995. When broken or abnormal, these genes predispose women to breast and ovarian cancer. The breakthrough was a catalyst to the field of cancer genetics.

“This was perfect timing to have love for cancer genetics kindled,” Ross says.

“I not only fell in love with the science of cancer genetics, but I was a medical resident and then oncology fellow,” Ross says. “This was perfect timing to have love for cancer genetics kindled.”

Ross’ kindled love for the developing field quickly grew to a blaze. After her MD and PhD training, Ross strategically moved to do her postdoctoral training with Dr. Gary Gilliland at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Ross credits Gilliland, an expert in cancer genetics and precision medicine who serves as president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, for teaching her how to think about cancer genetics both at the tumor level (not inherited) and at the germline level (inherited).

“In parallel, my family had a lot of cancer cases. I was very happy to be not only an oncologist but also a researcher interested in genes that cause cancer,” Ross says.

Passion Becomes Personal

After years of practicing oncology and high-level development in cancer genetics, Ross’ passion became personal. Ross was unsure whether to attribute her family’s many cases of cancer to genetics or mere misfortune until she was diagnosed with melanoma. As someone with a dark complexion, melanoma made no sense, which helped Ross determine there was, in fact, genetic factors driving her family’s history of cancer.

“The experience with melanoma didn’t motivate me as much as one would think. It did mean I had a personal story to tell,” Ross says. “I remember when my family and I went through the drama of cancer and then finding a mutation I thought, ‘If this is still interesting in 10 years, I’ll write a lessons-learnt essay about it.’ Ten years later, I wrote the essay and based on that I got a book agent.”

Ross is ready to share her story and her research, hoping it will provide a key resource for those interested in or affected by inherited cancer. She is scheduled to address The Common Wealth Club of California in Palo Alto on February 23. She will then speak at an event for SXSW on March 15th.

“It also hit home to me that self-deception is common to most of us and memories of family histories are usually not based on fact,” Ross says. “Being a personal and family health investigator is a noble occupation that takes patience, skepticism, and sometimes benevolent manipulation.”

We connected with Dr. Theodora Ross. Keep reading to learn more about why she came to DFW, UT Southwestern’s work in cancer genetics, why she wrote the book, and for her thoughts on how we can battle cancer more effectively.

For a daily dose of what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth innovation, subscribe to our Dallas Innovates e-newsletter.