Uplift Education has developed a data-centric culture that goes beyond teaching kids to pass standardized tests. As Dallas-Fort Worth’s largest public charter school network, Uplift is utilizing more relevant, holistic, and accessible measures of academic performance in a collaborative fashion to transform its young scholars into rising stars. “Our data system gives our students, parents, and their teachers transparency into where a child is at, how they are progressing during the school year, and where they ended up at the end of the school year,” says Yasmin Bhatia, CEO of Uplift Education. “We want to empower students and families to know where their child is relative to their national peers and not just know if their child passed a STAAR exam.”

Part of that empowerment is Uplift’s network wide use of the Northwest Evaluation Association Measures of Academic Progress (MAP), which creates a personalized assessment experience for each of its scholars by adapting to their individual learning levels. MAP is more rigorous and relevant than standardized tests like STARR, as it precisely measures student progress and growth for each unique child.

And Uplift Education isn’t just teaching beyond a test; it’s acquiring meaningful data about its scholars and schools. “Often, when school districts think about data, they think about measuring assessments like a state or national exam,” says Rich Harrison, Uplift’s Chief Academic Officer. “While we work very hard to provide useful and actionable data dashboards around academic performance and growth and metrics tied to college readiness, we equally value data on how our teachers, scholars, and parent community feel.”

“Uplift very clearly sees its role as showing what is possible for our students regardless of their family’s economic situation or background,” Yasmin Bhatia says. “We don’t accept excuses for why kids can’t be successful.”

Founded in 1996, the Uplift Education network has grown to 34 schools that serve more than 14,000 pre-k to high school scholars (what the school systems calls its students), 74 percent of whom receive free or reduced lunch.

More important than where Uplift’s scholars are is where they are going: 100 percent of its graduating seniors are accepted into college every year.

“Uplift very clearly sees its role as showing what is possible for our students regardless of their family’s economic situation or background,” Bhatia says. “We don’t accept excuses for why kids can’t be successful.”

Building a Culture Around Data

Type the word “data” into the search bar in the top right corner of Dallas Innovates (after you finishing reading and sharing this story, of course), and a good number of education stories will pop-up. That’s because this digital platform is about innovation, and collecting and using student data to make informed choices about how schools, districts, and states prepare our future generation is where the educational landscape has been headed for some time.

“At Uplift, we have taken steps over the last four years to build a culture around data; one that is defined by meeting the academic and programmatic needs of our scholars, providing effective and real time tools for our teachers and leaders, and being transparent about the levels of performance and growth around college readiness and school/organizational effectiveness,” Harrison says.

Fourth-grade teacher Shannon Streiff and scholar Omar Odom at Uplift Hampton Preparatory. Photo by Brandon Thibodeaux.

When done correctly, the collection and analysis of student data can have a profound impact on the academic progress of children across all demographics and backgrounds.

Uplift uses the resources available to form a system that yields the best results for kids. Its leadership saw the advent of data-informed decision-making rising on the horizon of the modern educational landscape, and has since been working to build a culture informed by meaningful student and school data. Their first step was to look at industries that had already been implementing impactful data strategies.

“When I first joined Uplift, I had a couple of conversations with leaders outside of education—actually with healthcare leaders,” Harrison says. “I took the time to understand what data modeling and use cases looked like at large hospitals or for a software company building healthcare applications. These conversations shaped our vision as to what is possible in a public school setting.”

In addition to using MAPS to collect more rigorous, meaningful, and personalized information about its scholars’ academic progress, Uplift’s initial cross-sector conversations about data led to the prioritization of speed, accessibility, and collaboration.

“At Uplift, we use Tableau, a business intelligence and data reporting tool used by many Fortune 500 companies, at the teacher, school administrator, and network levels,” Harrison says. “For every core practice, there is an accessible data dashboard.”

Modeling its data accessibility after successful companies has and continues to afford Uplift’s faculty and staff on-demand access to important metrics about its schools and students. By taking a page from the world outside of education, Harrison and his colleagues can answer complex questions, for example which of Uplift’s 34 schools had the strongest growth on the math section of the ACT from those students starting the school year below college readiness in 11th grade. An important step forward for the data-centric educational culture that will only grow in the coming years, especially when considering STAAR and other standardized tests often take weeks to months to return data, rendering them far less effective.

“I took the time to understand what data modeling and use cases looked like at large hospitals or for a software company building healthcare applications,” Harrison says. “These conversations shaped our vision as to what is possible in a public school setting.”

“It allows our educators to answer questions about performance and growth very quickly—often within a few clicks,” Harrison says. “We prioritize ‘speed to market.’”

In addition to fast-tracked accessibility, Uplift’s data-model is also built upon collaboration. Early on, the school system committed to creating one location where its teachers and leaders could interact with data sources that painted a clearer picture of student, teacher, and school performance. To further promote collaboration, Uplift now brings its 800 educators together three times a year, where together they analyze their students’ data in depth. “We participate actively in data conferences so that we are always learning, sharing, and innovating,” Harrison says.

Uplift’s culture of accessible data, and emphasis on teamwork, has also opened new doors for how teachers are able to grow. “For our teacher support and coaching, we have a dashboard that documents the number of coaching touchpoints each teacher receives (the average Uplift teacher receives seven coaching observations each semester), metrics relating to our classroom instructional and culture indicators, and a way to journal a teacher’s action steps to see their development and coaching over the course of the year,” Harrison says.

The Whole Scholar

The steps Uplift has taken toward embracing academic performance data has, at the very least, aided its schools’ and scholars’ notable achievements.

Uplift successfully met the 2015 Texas Education Agency accountability ratings. That same year, four of its schools earned all seven possible TEA accountability ratings distinctions.

As for the scholars’ performance, Uplift’s class of 2015 collectively performed above the national college readiness benchmark on the ACT, while the percentage of Uplift scholars who passed the STAAR Reading and Algebra tests was above the state average for all grades tested.

“We’ve found, particularly with our scholars, that they rise up and truly thrive under a culture of higher expectations complimented with meaningful support from our teachers to reach those goals,” Bhatia says.

Dr. Rhonda Hyde, ninth-grade biology teacher, and ninth graders, Yulissa Alvarez and Rachel de-la Paz at Uplift Williams Preparatory. Photo by Brandon Thibodeaux.

But Uplift does not just look at the STAAR results. It considers the entire scholar in its pursuit to make each one of them more than a percentage, number, or stat. Uplift knows that behind data are kids—specifically, the rising stars of tomorrow. And the school system knows that teachers and parents are integral parts of a collective mission to prepare Uplift’s scholars for success in college, career, and community.

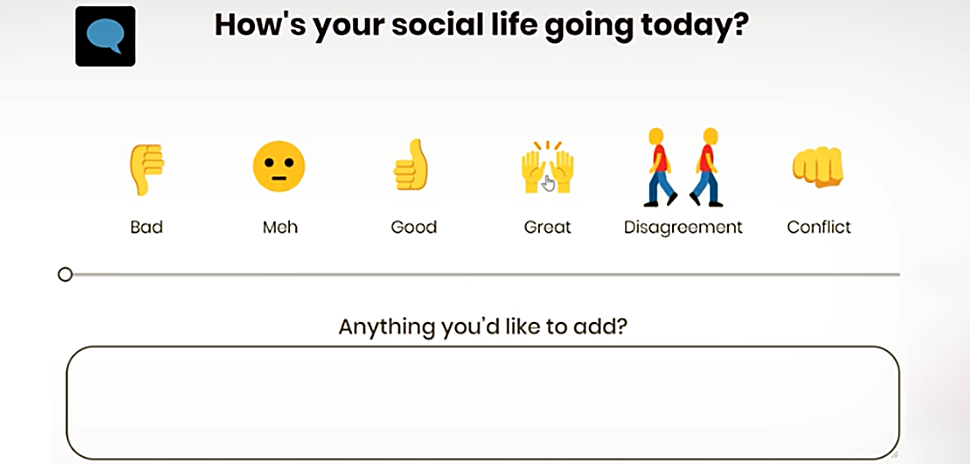

“We give surveys and collect data quarterly to better understand our teachers’ needs at an organizational and individual school level around; we collect yearly data from our parent community so that we can better meet their needs,” Harrison says.

“The most important thing we want to achieve is our broader community asking of their public schools ‘Why can’t every child in our district be on a path to go to college?’ so a new higher expectation is set for all schools and students,” Bhatia says.

And the Uplift network is using the success of its parent and teacher surveys to implement student surveys in an effort to better assess how its scholars perceive their school, learning experiences, and cultural belonging, as well as non-cognitive skills such as grit, mindset, learning strategies, and emotional regulation.

“Over the last six months, we have piloted a student survey instrument through Panorama that collects data on social-emotional learning,” Harrison says.

By the year 2020, Uplift projects its schools will be educating upwards of 20,000 scholars across Dallas-Fort Worth. The network’s leadership and faculty will continue to evolve the data system in pursuit of seeing 70 percent of its alumni graduating from college within six years.

“The most important thing we want to achieve is our broader community asking of their public schools ‘Why can’t every child in our district be on a path to go to college?’ so a new higher expectation is set for all schools and students,” Bhatia says.

For a daily dose of what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth innovation, subscribe to our Dallas Innovates e-newsletter.