What makes a neighborhood safe, livable, and economically viable? Good infrastructure, says a new study from Southern Methodist University—things like crosswalks, noise walls, grocery stores, hospital access, bike trails, and more.

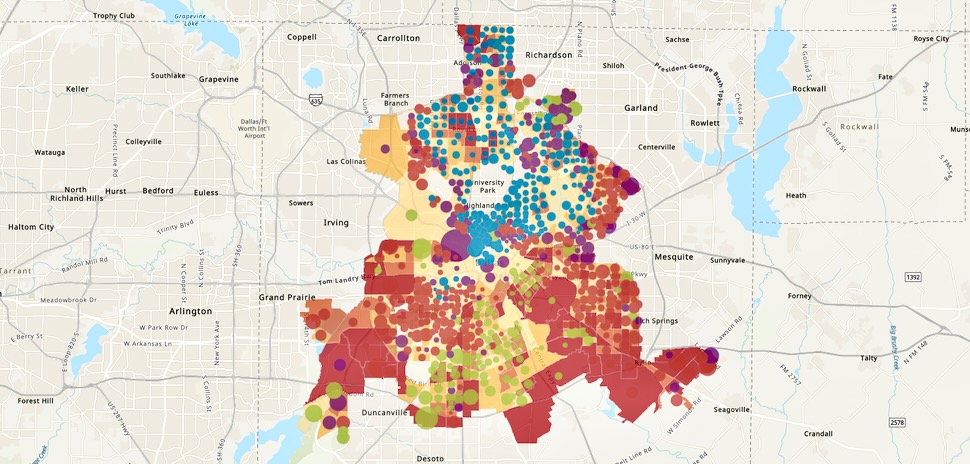

A team of civil engineering researchers at SMU has identified 62 Dallas neighborhoods as “highly deficient” in infrastructure, resulting in “infrastructure deserts” that lessen the quality of life for their residents. As seen in the dark red areas in the map above, most of the neighborhoods are located in the southern part of the city and are home to primarily low-income, Black and Hispanic residents.

The study was supported by a five-year, $584,000 National Science Foundation grant which funds the development of open-source data management software called Clowder, a web-based content repository for finding and utilizing data, which was developed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

SMU Professor Barbara Minsker led a team of 20-plus researchers. [Photo: SMU]

A need for ‘smaller-scale infrastructure at the neighborhood level’

“Often infrastructure funding is used for major investments, like freeways or airports,” said Barbara Minsker, the SMU professor who led the study, in a statement. “This study shows the importance of funding for smaller-scale infrastructure at the neighborhood level.”

Minsker, who’s the Bobby B. Lyle-endowed professor of leadership and global entrepreneurship in SMU’s department of civil and environmental engineering, worked with Ph.D. student Zheng Li and a team of more than 20 researchers on the project.

The team created a computer framework with the ability to assess at census-block level 12 types of neighborhood infrastructure. Using this framework, they evaluated and compared neighborhoods by infrastructure deficiency, household income, and ethnicity.

Nearly 800 Dallas city neighborhoods were rated on the condition of their streets, sidewalks, Internet access, crosswalks, noise walls, street tree canopy, public transportation access, hospital or medical service access, bike and pedestrian trails, community gathering places, and food access. Each neighborhood was rated excellent, good, moderate, deficient or highly deficient.

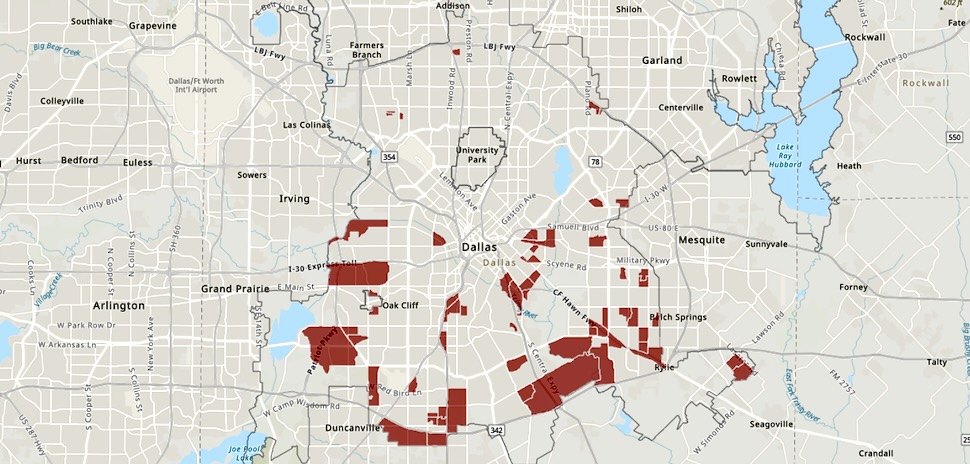

Infrastructure deserts seen in isolation, from the SMU study. [Image: SMU]

Drones and machine learning helped generate data

The team has produced interactive reports with maps and graphics that help explain the disparities in infrastructure, and why the areas in dark red in the map above are “infrastructure deserts.”

Much of the data used in the research was publicly available. But other data was generated by machine learning, using aerial images to detect crosswalks and assessments of Google Street View images to identify noise walls.

Undergraduate and graduate researchers used technology such as drones, smart phone apps, and artificial intelligence to gather data. They also used “feet-on-the-ground” techniques including driving tours of the city and brainstorming sessions with community groups to define the concept of infrastructure deserts.

The study’s key findings

• Low-income neighborhoods in the city of Dallas are up to 3.5 times more likely to be infrastructure deserts—highly deficient in eight or more types of infrastructure—than high-income areas.

• Majority Black neighborhoods are up to 4.6 times more likely to be infrastructure deserts than majority white areas.

• Majority Hispanic neighborhoods are up to 3.5 times more likely to be infrastructure deserts than majority white areas.

• A significant percentage of infrastructure deserts are located in the southern portion of the city, south of I-30.

• Common deficiencies across Dallas neighborhoods, regardless of income level or race, include sidewalks, street tree canopy, food access and medical service access.

The two low-income areas with the most deficiencies—10 out of 12—are south of I-30, one in Southwest Dallas, the other in Southeast Dallas. The two neighborhoods with only one deficiency were located in high-income areas, one southwest of Highland Park, the other a high-income area of Oak Cliff.

Southern Dallas has been an increasing priority for the city

Southern Dallas has been an increasing priority for the city in recent years, with projects underway like the Southern Gateway I-35 Deck Park in Oak Cliff, $21 million in federal RAISE grants supporting three local projects, funding by the Dallas Regional Chamber for 13 organizations to elevate Southern Dallas County, and more.

Private investment is helping as well, with efforts like a $1 million AT&T grant to Southern Dallas Thrives, Emmitt Smith and UNT Dallas opening an expansion of the Southern Dallas Innovation Center, and the Dallas Mavericks’ dedicating its largest tech center to date at the campus of For Oak Cliff.

Now Minksy and her team are hopeful that their study will lead to more widespread infrastructure improvements where they are needed most.

Several city offices have requested the data

Minsker and her team are having discussions now with local policy makers with a goal of using their study to spur change, perhaps with the next city bond proposal.

“Several city offices have requested our data and more details on the approach so that they could consider it in their decision making,” Minsker said. “One is the office that is preparing the next bond proposal. I’ve also reached out to several nonprofits that work in the areas with infrastructure deserts and have two meetings set up. There is certainly enough interest that I expect the information will be used.”

The study is more detailed than previous similar studies, Minsker says, which is one reason it may get more traction.

“Prior to this study, there was no fine-grained quantitative information about neighborhood infrastructure and equity across the city that could be used to drive policy making and investment decisions” like bond projects, Minsker said.

Infrastructure deficiencies worsen impacts of storms, pandemics

When major shocks hit a city, areas with poor infrastructure suffer the most, Minsker says.

“We saw poor access to medical care and public transit as major problems affecting access to health care during COVID,” she said in the statement. “Lack of Internet access interrupted the education of thousands of school children. We also saw subtler effects. The lack of community gathering spaces reduces community support, which affects resilience and health. Lack of access to parks and trails can decrease mental and physical health, particularly when COVID prevents many other activities.”

Inspired by a Habitat for Humanity city tour

Minsker began teaching at SMU in 2016 after her prior post at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“A major part of the attraction was to be able to study issues in a major city like Dallas,” she told Dallas Innovates. During her first year in Dallas, Minsker was given a city tour of low income neighborhoods by a staffer from Habitat for Humanity which “provided much of the inspiration for this study,” she said. “They mentioned significant infrastructure issues that have impeded their housing projects in Dallas.”

A nationally recognized expert in environmental and infrastructure systems analysis, Minsker saw Dallas as a “living laboratory” to develop a test case for the Clowder content repository. By creating a framework that could analyze data from multiple sources to understand the equity and inequity of Dallas’ infrastructure, Minsker aims to use engineering to improve community and ecosystem health and well-being. That’s also the objective of SMU’s Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity, where Minsker serves as a senior fellow.

‘Meaningfulness’ is in the stories created by patterns in the data

The study’s co-authors, Janille Smith-Colins, Xinlei Wang, and Jessie Zarazaga, significantly contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and presentation of the data, SMU said. For Ph.D. student Zheng Li, the meaningfulness of this research is in the stories created by patterns in the data.

“This framework enables us to collect data from a huge variety of sources, then analyze the patterns that emerge to discover new information that can be used by scientists, policy-makers and residents to improve their neighborhoods,” Zheng Li said in the statement.

Other cities will be studied next

The next steps for the study team will include publishing the research results in academic journals and using the framework to study other, even bigger cities—such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.