Scientists at Children’s Medical Research Institute at UT Southwestern have identified the niche—a specialized environment where new bone and immune cells are produced—located in bone marrow, leading to a discovery that shows movement-induced stimulation is necessary to maintain the bone and immune-forming cells it contains.

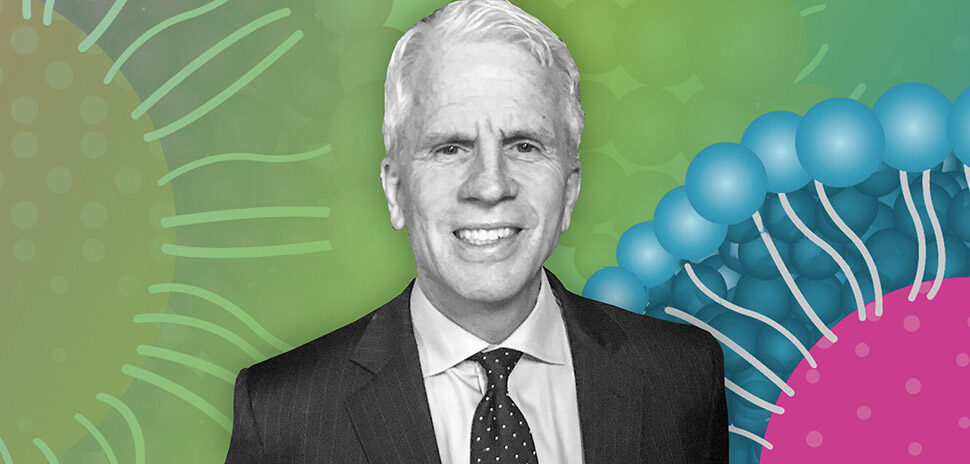

“As we age, the environment in our bone marrow changes and the cells responsible for maintaining skeletal bone mass and immune function become depleted. We know very little about how this environment changes or why these cells decrease with age,” Director of CRI Sean Morrison, Ph.D., said in a report on the discovery.

In the past, research has shown exercise can improve bone strength and immune function, but the newly released study shows a novel mechanism by which this occurs, according to Morrison.

By walking or running, mechanical forces are created and transmitted from bone surfaces along arteriolar blood vessels into the marrow inside bones. The bone-forming cells, which line the outside of the arterioles, sense the forces and are induced to reproduce rapidly.

This allows for the formation of new bone cells that help thicken bones, but also secretes a growth factor, which increases the frequency of cells that form lymphocytes, B and T Cells that allow the immune system to fight infections, around the arterioles.

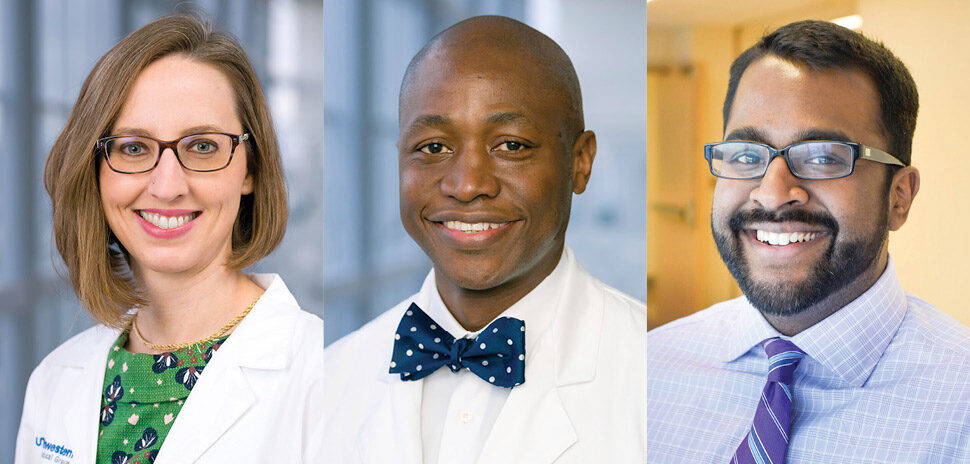

In previous work, CRI scientists from the Morrison Laboratory discovered Leptin Receptor+ or LepR+ cells, which are skeletal stem cells that give rise to most of the new bone cells that form during adulthood in the bone marrow. They also previously found an undiscovered bone-forming growth factor called Osteolectin, which promotes the maintenance of the adult skeleton by causing LepR+ to form new bone cells.

In this new study, Bo Shen, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow in the Morrison Laboratory, discovered that Osteolectin cells are exclusively located around arteriolar blood vessels in the bone marrow. They maintain nearby lymphoid progenitors by synthesizing stem cell factor (SCF), a growth factor that those Osteolectin depends on.

“Together with our previous work, the findings in this study show Osteolectin-positive cells create a specialized niche for bone-forming and lymphoid progenitors around the arterioles,” Shen said in a statement. “Therapeutic interventions that expand the number of Osteolectin-positive cells could increase bone formation and immune responses, particularly in the elderly.”

Shen found that as we age the number of Osteolectin-positive cells and lymphoid progenitors decrease.

And, that putting running wheels in the mice cages so they could exercise strengthened the mice’s bones. That led to an increase in the number of Osteolectin-positive cells and lymphoid progenitors around the arterioles.

This indicated that mechanical stimulation regulates a niche in the bone marrow.

Osteolectin-positive cell express a receptor called Piezol on their surface that signals inside the cell in response to mechanical forces. Without Piezol in Osteolectin-positive cells, these cells and the lymphoid progenitors they support became depleted, which weakened the bones and impaired immune responses in the mice.

So, why is this important? The study shows that exercise can reverse the trend of our bones become thinner and our immune system declining as we age. Because the cells responsible for maintaining skeletal bone mass and immune function get depleted over time, CRI has proven that these cell types can increase with exercise, helping to strengthen bones and promote immunity.

To Morrison, it’s “an important mechanism by which exercise promotes immunity and strengthens bones, on top of other mechanisms previously identified by others.”

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.