Dallas-Fort Worth has grown consistently over the past few decades. But, Walter Bialas says, the benefits of this growth haven’t been evenly distributed.

That’s why he and his team at JLL have released a new report that delves into the imbalances across the region. Bialas, the vice president of market research at JLL, believes data has the power to raise awareness and show opportunities for positive change.

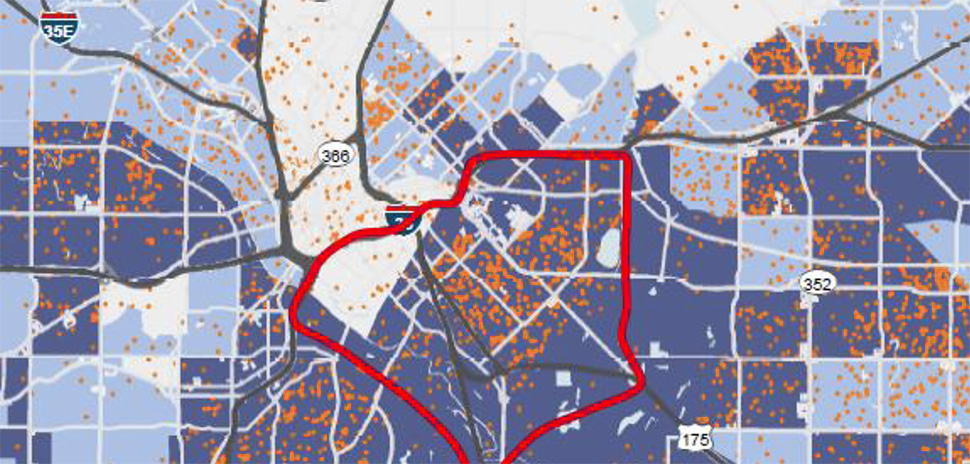

In his newest JLL Snapshot, Bialas looks at South Dallas to better understand how it evolved into a food desert.

The United States Department of Agriculture defines a food desert as a place with people who have limited access to healthy and affordable food, a poverty rate higher than 20 percent, and a third of the population that is more than a mile from a major grocer. JLL notes that these areas often don’t have a ton of vehicle availability or adequate public transit either.

There are around 6,500 census tracts that are food deserts, according to the USDA. The department included South Dallas within that list.

But the area wasn’t always like it is today, Bialas notes. Back in the 1940s, it was classified as a middle-to-affluent neighborhood.

“After WWII the neighborhood began to change. As growth began to push north, many households relocated, creating new neighborhoods like Highland Park. Lower income, black households began to move to South Dallas,” he writes. “Like many cities across the US, the 1950s suburbanization saw new highways planned and built to channel growth. For South Dallas, the creation of I-30 and I-45 destabilized the area greatly.”

JLL points to a few different factors that contributed to the neighborhood’s isolation: I-45 cut the 11-square-mile neighborhood in half, I-30 disconnected it from the CBD’s job base, and the Trinity River forest’s boundaries separated it from the rest of the region.

South Dallas’ food desert [Source: JLL]

Bialas says over the decades, that isolation “exacerbated the differences that were emerging.”

JLL data shows that 11,600 households are in South Dallas, which hasn’t changed from 2000. The average household income is $42,000, with 60 percent earning less than $35,000. JLL points out that the average in DFW is $96,000.

Add to that the statistics related to food.

Most of the grocery shopping occurs at small neighborhood markets and convenience stores, making the area a “true food desert,” according to JLL. Residents are disproportionately spending their money because of the high pricing and limited food options at these types of places. Bialas notes that one of the largest stores is the 14,000-square-foot Save A Lot.

“Food deserts like these carry many repercussions—the most basic being that residents have few healthy food options, which impacts wellness. Affordability is another major and often overlooked problem,” Bialas writes. “Due to their incomes, combined with higher prices at these outlets, people in the bottom income intervals spend a disproportionate amount on the basics that most of us take for granted.”

JLL data shows that those in the bottom 20-30 percent of income-bands pay 14-16 percent of their income on groceries. Compare that to the 6 percent for the average US consumer.

“Despite these challenges, residents generate $58 million in grocery spending—sufficient to support three full-scale grocers,” JLL says. Some sales do take place outside the area, according to Bialas, but he points out that many of these households have limited access to vehicles and DART stations.

“This reinforces the patterns of the past,” he writes.

JLL offers solutions

Following its analysis, JLL offered a few solutions that could assist with the food desert dynamic. The company says it won’t change without public support, though.

“Our review of South Dallas indicates that this food desert situation will not change on its own,” Bialas writes. “Even though the neighborhood is small and isolated—potential does exist.”

JLL’s first idea is to “create a cushion to support a grocer at ‘breakeven.'” This would be engineered as a “community good” from the public and private sectors.

A public-private partnership would involve direct dollar subsidy to encourage a new grocer, rather than using a one-time, direct dollar subsidy. Bialas notes that the key is breakeven: “in this way, the public minimizes risk by defraying overhead costs as necessary and the private operator runs the store for a community good.”

He says this could seed the area for social change in the future, while also creating more healthy and potentially more affordable alternative food options.

Bialas also points to a few projects already underway. Paul Quinn College recently turned its football stadium into an urban farm. The Dallas Farmers’ Market was rebuilt, and is located nearby.

“But these are only a beginning,” he writes. “With this much grocery spending being generated, the neighborhood will support as many as a few downsized traditional grocers. The issue is sales risk for these operators.”

While JLL has come up with a few ideas, Bialas and his team want to continue the dialogue and invite anyone to contact them with feedback and ideas.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.

![Pudu offers many commercial service robots. Free 1-week trials of the PuduBot food delivery robot (far right above) are being offered to Dallas restaurants for a limited time. [Image: Pudu Robotics]](https://s24806.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Pudu-Robotics-970x464.jpg)