The Shadow CEO is an ongoing series with tips for entrepreneurs from serial founder and high-tech industry veteran Dennis Cagan, who has served on sixty-seven for-profit corporate boards, including ten publicly traded companies.

Many first, second, and even third-time founders get themselves into bad situations that could be avoided if they knew more about how corporate governance and equity distribution worked in early-stage companies.

![]() Whether you hope to eventually sell your start-up to a larger firm or navigate through an IPO, if you plan on taking in investors—friends and family, angels, venture capital, or strategic corporate investors—you need to understand how to protect yourself and your management team.

Whether you hope to eventually sell your start-up to a larger firm or navigate through an IPO, if you plan on taking in investors—friends and family, angels, venture capital, or strategic corporate investors—you need to understand how to protect yourself and your management team.

The segments in this ongoing series can not only save you time and energy, but they could result in making—or saving—you millions of dollars.

Determining Valuation

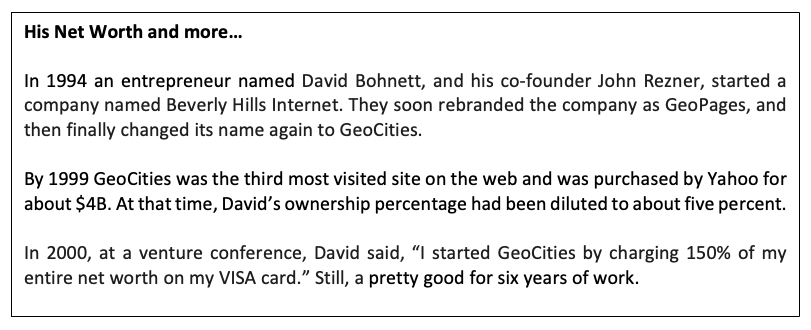

In 2000, I founded a full-service incubator and a venture capital firm, raised capital, and started investing in technology start-ups full-time (ultimately about 40).

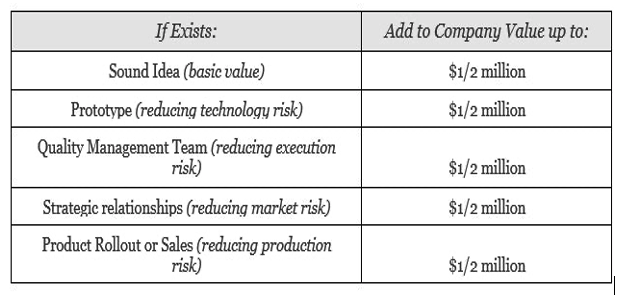

One day during a meeting with an entrepreneur, I asked what he was seeking for a pre-money valuation. Without hesitation, he said $2.5 million. I asked him how he arrived at that. He confidently responded, “The Berkus Method.” I said, “What?” The entrepreneur said, it’s something published by someone at Harvard.

Well, I had been in the business for a long time, even at that point, and I had only ever met two guys named Berkus, and they were brothers. I asked the entrepreneur if it had anything at all to do with a ‘Dave Berkus’? He said he had no idea, except the method was published by Harvard.

When I checked into it, sure enough, it was my old friend Dave, who I had done business with in the ’70s. The attraction of the method is very simple—each of five milestones is awarded up to half a million dollars, depending on your subjective level of achieving that objective. Full accomplishment thereby would yield $2.5 million.

While this overly simple approach may help serve as one element in testing the validity of a valuation, few investors will really give it much credibility. It is simply not nuanced enough for any experienced ones.

Each of the five components needs to be broken down and measured objectively. The most effective way to gauge a more accurate pre-money valuation, or the FMV, is direct ‘comps’—comparable numbers and metrics from other companies as closely related to yours as possible in the areas of products/services, market size, stage of product development, funding history, comparable management team, number of users, number of paying customers, total revenue, profit (if any), and more. Keep in mind that the ultimate arbiter of the value of your enterprise is the investor or buyer. This is the most reliable way of gauging an investor’s or buyer’s appetite.

Beyond comps, there are a variety of other metrics, including some multiple (1X, 2X…10X) of trailing (looking back over time) revenue, and or EBTIDA (profit), leading (looking forward over time) revenue or profit. The multiple usually depends on the current transaction environment and normally varies by industry and sector.

One interesting exercise that I like to encourage is the following: It is almost certain that an investor would buy your company for $1.00, assuming at least that there are no liabilities. In the same vein, it is unlikely that one would pay $1 billion for it.

The idea is that the right price—for investment or sale—lies someplace in between. The closer that the number an investor is willing to pay is to the number that you are willing to accept, the more likely a deal—obviously.

The point is, if it’s your company, or you are CEO or simply own controlling interest, the price at which you are willing to accept investment capital or sell the company, is set by you, with board approval if necessary. Certainly, current opportunities or difficulties may weigh your decision on valuation either up or down, but it still remains yours. Now that must coincide with what the investor is willing to pay. That is where art and science meet—setting your valuation and then justifying it with the firm’s exciting accomplishments and prospects, and some quantifiable quasi-standard metrics.

Valuation Methodology

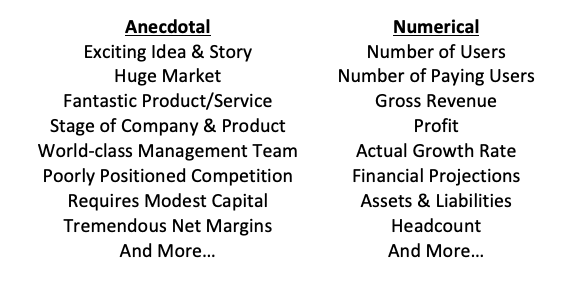

There are two kinds of information that goes into the valuation of an early-stage company—or any company—anecdotal and numerical.

Anecdotal details are a combination of fact and vision. Successful delivery of these messages depends on their veracity and the skill and charisma of the deliverer of the message. A good story creates the motivation for the investor to be interested at all. Without connecting on this, it’s unlikely that any investor would even care to hear the numbers.

In terms of numbers, the only ones that all early-stage companies do well on are … expenses. Unfortunately, the investor expects that, but is not interested. It does not help the valuation narrative. To be perfectly clear, many companies have raised money with few or no actual numbers.

However, for the most part, if an entrepreneur is starting their first venture, even if they have a decent track record of working for other companies, and they are lacking extensive connections, or they don’t normally associate with discretionary wealth, they will need to do it the hard way—bootstrap. That means scraping together some money and some colleagues and just starting. As mentioned above, the easiest and usually first money available is friends and family, called that for obvious reasons.

If one can use those seed funds to prove out the business concept—and hopefully even generate some actual numbers—then the opportunity to raise additional capital becomes more achievable.

Note: The information provided in this article does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal or tax advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available below are for general informational purposes only. Information in this article may not constitute the most up-to-date legal, tax, or other information. Readers should contact their attorney or CPA to obtain advice with respect to any particular matter. The views expressed here are those of the author writing in his individual capacity only.

MORE SHADOW CEO

PART 1: Early-Stage Insights for Entrepreneurs

PART 2: Deciding to Distribute Startup Equity? Here’s a Founder’s Guide

PART 3: Using Equity as an Incentive and the Role of the Board

PART 4: What Entrepreneurs Need to Know About the Foundational Documents of a Corporation

PART 5: Equity Distribution Techniques

PART 6: Equity Beyond Stock Options

PART 7: Stock Classes and Raising Capital

PART 8: Determining Startup Value

PART 9: Explaining Common Metrics

PART 10: Calculating Share Price

PART 11: Protecting Founders and Special Voting Preferences

PART 12: Additional Equity Grants

About the author:

Dennis Cagan, a noted high-tech entrepreneur, executive, and board director, has founded or co-founded more than a dozen companies and served as CEO of both public and private companies. The venture capitalist, private investor, author, and consultant, is a long-time board member of some 67 corporate fiduciary boards. In his Shadow CEO® role, he steps in side-by-side with a CEO to help them navigate circumstances and situations on a day-to-day basis.

A version of this column was previously published in Cagan’s “A Primer on Early-Stage Company Equity.”

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.