Although they may seem unrelated, the landing of men on the moon and the start of UT Dallas are actually tightly linked. In fact, according to a 2009 interview with Dr. Francis “Frank” Johnson—an expert in atmospheric physics and UTD’s first acting president—UTD might have never been created had it not been for the U.S. space program.

Before it became UT Dallas, the university was known as the Southwest Center for Advanced Studies (SCAS). As a graduate-level research institution, SCAS was originally intended to attract STEM scholars and scientists to the region. In its early days, much of the center’s work was related to space sciences.

Throughout the years, SCAS contributed significantly to the U.S. space program, from training Apollo astronauts to designing space-based equipment that alerts astronauts of radiation hazards.

A look into SCAS research stars

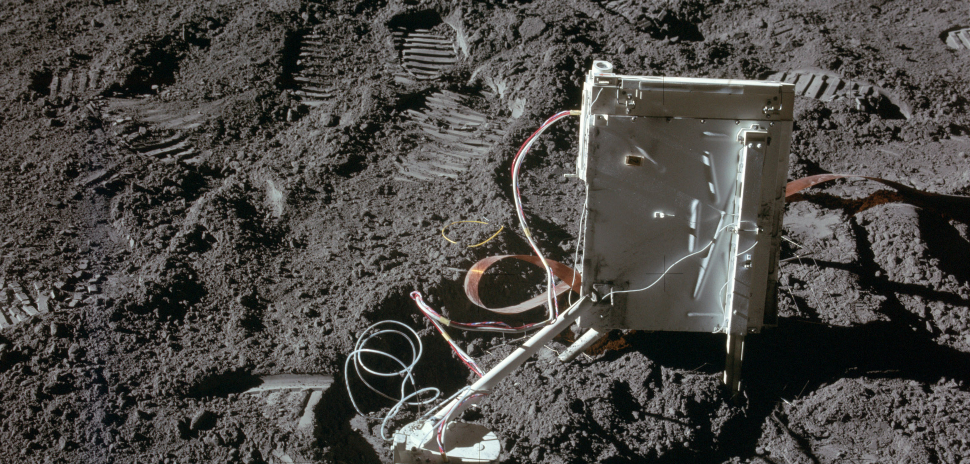

Dr. Johnson, who was recruited to SCAS in 1962, led the center’s research program in space and atmospheric physics. He designed experiments for NASA that could detect the existence of a lunar atmosphere in preparation for the first manned lunar landing in 1969.

His invention was a 3-pound, cold cathode ionization gauge that tested for atmospheric pressure on the moon, which flew on Apollo flights 12, 14, and 15.

Dr. Johnson’s cold cathode ionization gauge. [Image: Courtesy NASA]

However, Dr. Johnson was not the only SCAS researcher with a connection to the Apollo missions.

Dr. James Carter, who joined the center in 1964, used his expertise in geology to help train Apollo astronauts on what to look for once they landed on the moon.

“No one had a firm idea what the astronauts would find on the moon, so we gave them broad field research experience over a couple of days,” Dr. Carter said in a statement.

In addition, Dr. John Hoffman, who joined in 1966 and is now retired as a professor of physics at UT Dallas, built space instruments that accompanied the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions.

The start of UT Dallas

While space science efforts at SCAS were largely supported by grants, other research areas such as geosciences and molecular biology had funding that was less stable. Joining the UT system would bring in financial support from the state, which prompted SCAS to become The University of Texas at Dallas on Sept. 1, 1969.

Despite the switch, UTD has continued to stay true to its SCAS roots with a continued commitment to space sciences.

In 2017, researchers at UTD’s Center for Robust Speech Systems in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Sciences completed a five-year project to analyze communications between astronauts, mission control specialists, and back-room support staff during the Apollo missions, which was led by Dr. John H.L. Hansen.

According to Dr. Hansen, this included audio that had never been heard before. On top of digitizing these communications, advanced speech diarization technology was developed to settle the question of “who spoke what and when.”

Over the past 50 years, it’s clear that UTD’s space science program—and the innovations that have come from it—have made significant contributions to our understanding of space and its applications to life on Earth.

“Between now and then, our space research program at UT Dallas has been able to continue to work on research areas that are important to society,” Dr. Rod Heelis told Dallas Innovates, director of the William B. Hanson Center for Space Sciences at UTD.

Currently, the focus of UTD’s space research is largely concentrated on understanding how the space environment affects communication and navigation systems.