The National Math and Science Initiative already has made great strides spreading science, technology, engineering, and math curriculum to thousands of classrooms across the country.

The National Math and Science Initiative already has made great strides spreading science, technology, engineering, and math curriculum to thousands of classrooms across the country.

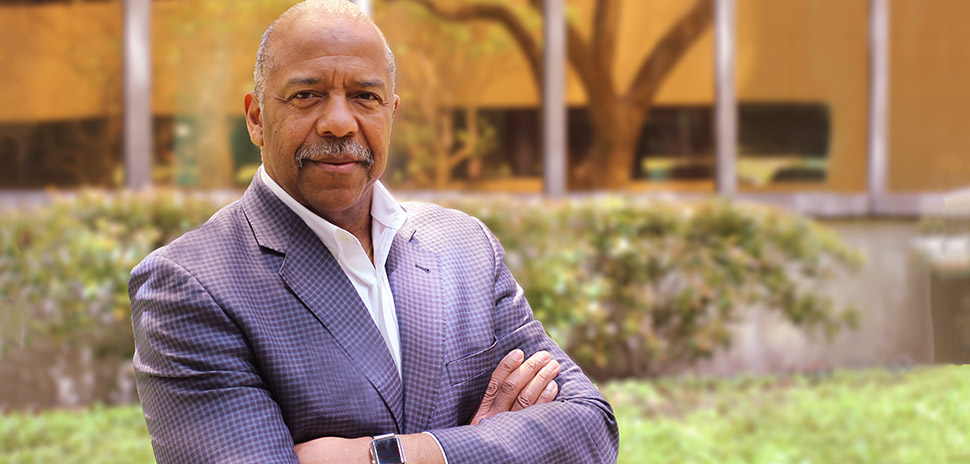

Now, under the leadership of former astronaut and physiologist Bernard Harris Jr., NMSI has partnered with Sylvan Learning to bring STEM education to Sylvan campuses nationwide.

Former astronaut Bernard Harris (right) signs an agreement with Sylvan Learning Centers. [Courtesy Photo]

Dallas-based NMSI was founded in 2007 to encourage STEM education in young people, particularly women and minority groups, by providing teacher training, establishing programs, and encouraging the next generation of teachers by creating a STEM pipeline in universities.

Harris, who took over as NMSI CEO last fall, was the first African-American to walk in space. He logged 550 hours there while studying the effects of space on humans and other organisms.

Former astronaut Bernard Harris (right) during one of his missions to the International Space Station. [Courtesy Photo]

Dallas Innovates talked with Harris recently about the partnership with Sylvan, the importance of STEM education, and what it’s like walking in space.

You’ve been with NMSI since the beginning 11 years ago. Did you ever envision yourself in the role of CEO?

Being on the founding board has been great. Watching it grow has been tremendous. We had tremendous leadership through the years. So I’m very honored that the board asked me to step in as CEO. I didn’t see myself in this role, but this is not foreign to me. I’ve been involved in providing STEM education for years.

How has NMSI’s role changed over the last decade?

The major thing is a decade ago it was finally recognized by the nation that we had an issue with our kids being ready for jobs where technology is at the heart of it. There was a call to action. That was the reason the National Math and Science Initiative was begun to address that.

We’ve started programs that have been proven to positively impact communities across the counties. The thing I’m most proud of is the expansion of our programs all across the country. Over 2 million students, 50,000 teachers, over 1,000 schools we’ve impacted. We’re in 44 universities working on that teacher pipeline.

The higher paying jobs are the STEM-related jobs. There are jobs in technology and engineering.

What can be done to better prepare our STEM workforce of tomorrow? How do we encourage young people, especially women and minorities, to enter STEM fields?

We have to start early for sure and that’s what our programs are all about. We start in third grade. We use professional development for teachers to help them more effectively handle STEM education and programs. It’s important with that age group that you connect the dots for students and you get them engaged.

It’s OK to be a geek. The innovators running these companies, they’re all geeks — geeks rule the world.

Girls and minorities sometimes are not encouraged to go into STEM. We have to change that mindset. It’s OK to go into these STEM fields. This is sort of a joke that I use when I talk with young kids: It’s OK to be a geek. The innovators running these companies, they’re all geeks — geeks rule the world.

We have to inspire them, aspire them, and give them the tools necessary so they can be competitive.

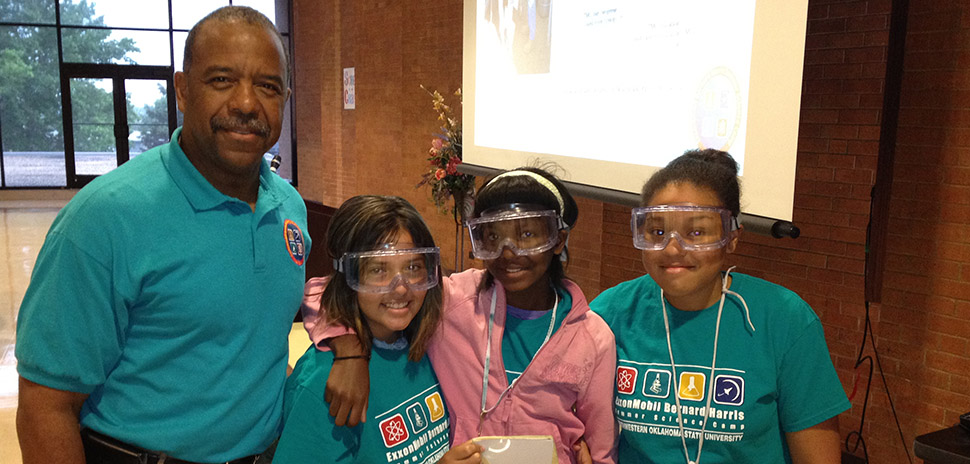

Bernard Harris poses with young learners at the ExxonMobil Bernard Harris Summer Science Camp. [Courtesy Photo]

As we get more technological and we have more AI, robotics, the workforce is going to change and it’s going to have to change its skill. They’ll go from building things to actually running computers that control the robot.

What does the new partnership with Sylvan mean for NMSI and the children who attend?

Sylvan has a number of centers across the nation. We see this partnership as a way to increase our reach. It’s another platform to deliver our content to more students. We both agreed that our priority is to reach into those economically disadvantaged areas.

We know for sure what we want to do is to come up with ways to implement more robust STEM programming that can be delivered in their centers. Also, they have content that they’ve developed that we can utilize in some of the schools that we work with.

There’s more to come.

Your background is fascinating and truly shows how far STEM can take you — all the way to space. Talk about how you can use your story to inspire today’s generation.

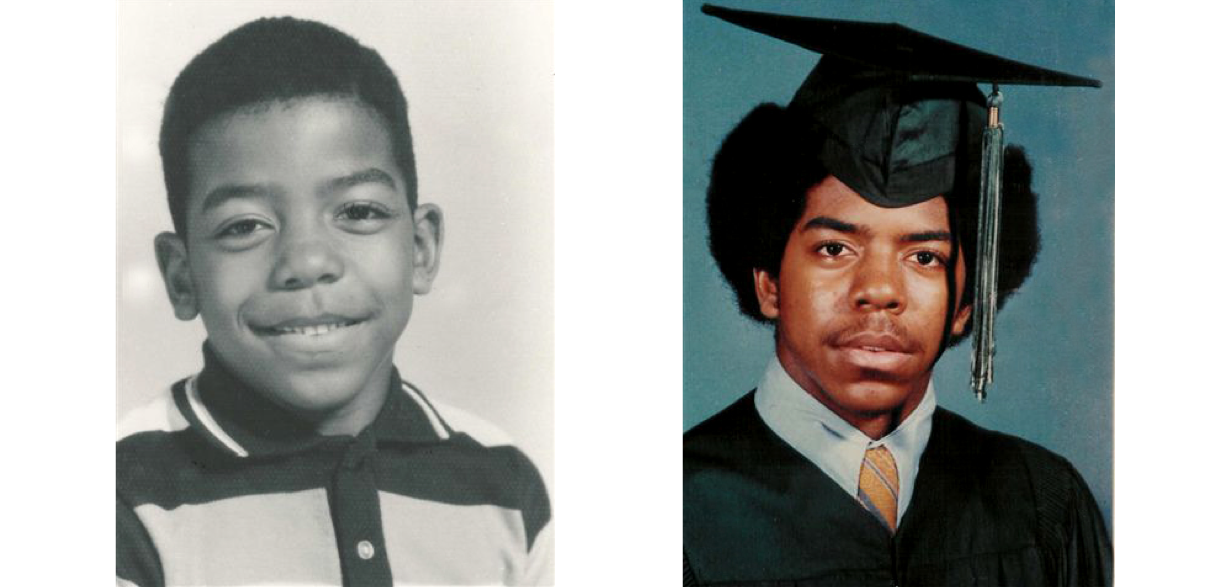

I grew up poor. The first six years of my life was in inner-city Houston, a very poor community. My mom was smart and got us out of that environment. She actually took a job being a teacher on the Navajo Nation, which is the largest Native American reservation. She taught us that education was the way. It was the way out for her, to get her family out of that environment.

My dream of becoming of an astronaut lifted me out of poverty.

In high school, I was following in the footsteps of the astronauts of the day. My dream of becoming an astronaut lifted me out of poverty. All my siblings are doing well in our respective fields.

Photos of former astronaut Bernard Harris in his youth. [Courtesy Photo]

Who inspired you as a young man to pursue medicine and, later, an astronaut?

Certainly, my mom is at the top of that list. She showed me the value of education. When I was in middle school, my science teacher was very inspirational. He was the one who made the rocket club. We also built a flying saucer. He got me involved in aerospace.

My inspiration for medicine was our family doctor, an African-American physician in San Antonio. And for astronauts, it goes without saying — it’s guys like Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin who were inspirational early on.

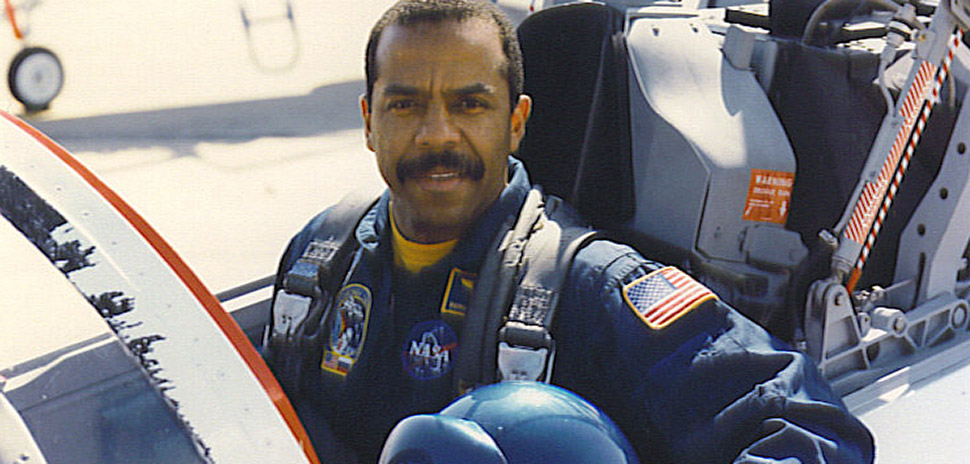

Former astronaut Bernard Harris in a jet trainer during his time with NASA. [Courtesy Photo]

What do you remember most about your time in space?

It was over 550 hours in space. 7.2 million miles. The most memorable flight was when I did the spacewalk. I put on the space suit, it was very bulky, very heavy — about 350 pounds. I walked outside and was outside for about six hours. You could see the spaceship, you could see the other astronauts inside the spaceship. You could see the Earth and behind that, you see all the stars in the Milky Way.

We were traveling at 17,500 mph. We could go around the Earth every 90 minutes. As long as I stayed relatively close to the spaceship, I could maintain that speed. If I got further than 100 yards, I would pull away from the vehicle. That’s all math and science I was just talking about, the orbiting mechanics.

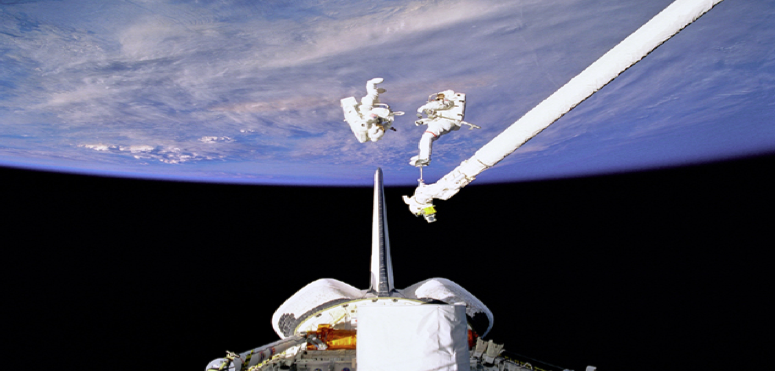

What was your mission?

Before the International Space Station was built, we had taken different components of the space station up to make sure it would work in the vacuum of space. We took the temperature in space.

[Courtesy Photo]

What goes through your head as your doing a spacewalk?

It certainly gives you a greater appreciation for life on this planet. You don’t see things that divide us. You don’t see the lines of latitude and longitude, you don’t see lines between countries.

You don’t see all the differences that we all seem to focus on. … It makes you feel kind of small, but also important at the same time.

You don’t see all the differences that we all seem to focus on. It reminds us that we are all Earthlings traveling on this spaceship called Mother Earth. We are one planet in our solar system. It makes you feel kind of small, but also important at the same time.

Your background was in musculoskeletal physiology. What did you learn about the prolonged effects of being in space on the human body?

That was my area of research. We tested that on animals, plants, and humans.

What we learned from our research, [is that] we lose 1 percent of bone mass per month and 10-15 percent of our muscle mass, especially in our legs and our antigravity muscles. We grow an inch or two in space, because of the unloading of the spine. We lose about one-fifth of our blood volume, which is OK as long as we stay in space. We become anemic — we lose red blood cells.

All of that that I just described is the body adapting to zero gravity. The longer you stay up, the more rehabilitation you have to go through when you come home.

![]()