Dallas artist Matt Cusick gave up paints in 2002, and never looked back.

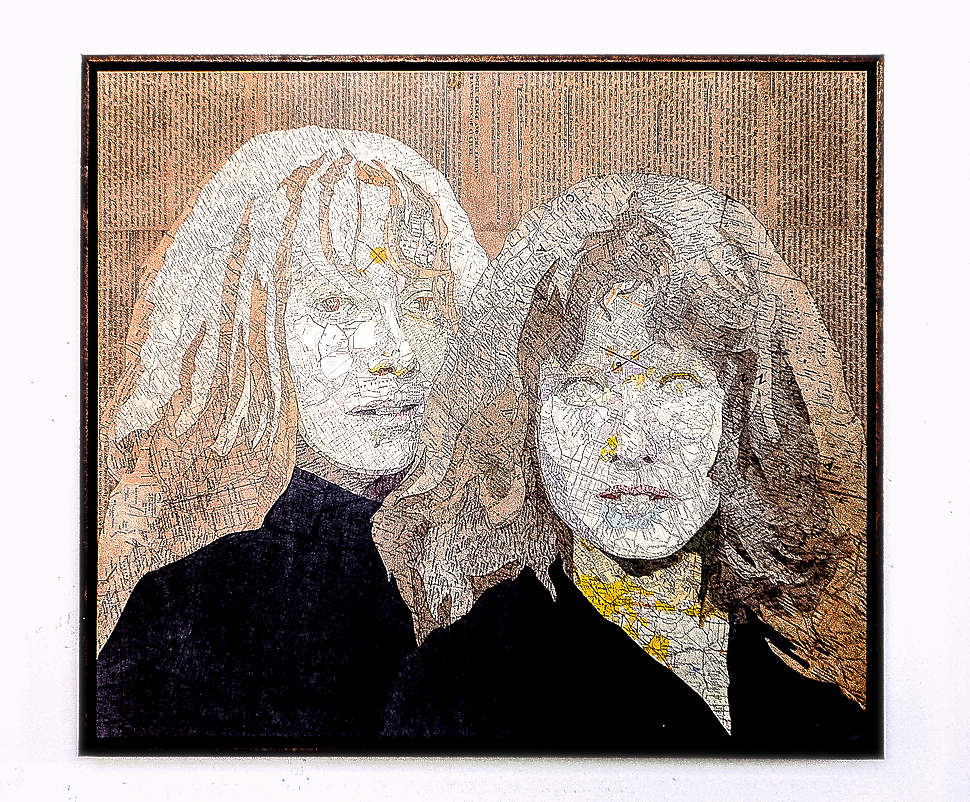

His quirky, inventive collages — humans, animals, water, and landforms — are crafted of recycled maps pieced together like a puzzle to create a new timeline infused with meaning.

Cusick’s process of “painting with maps” integrates science, art, and storytelling — or, as he says, the human condition. His aim is a new kind of cartography — an art that viewers read like a book.

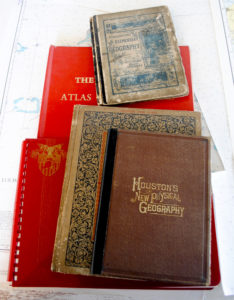

Inspiration for his signature work can be traced back to old maps he discovered at his grandmother’s house.

One day, frustrated by the limits of paints, Cusick picked up one of the maps of Dallas and stuck it on a photo of Bonnie Parker, the female half of infamous outlaw duo, Bonnie and Clyde.

“I [put it] right on her cheek where one of the big gun wounds would be,” Cusick told Dallas Innovates. “Boom — it was just like that. I told myself my next piece was going to be all maps.”

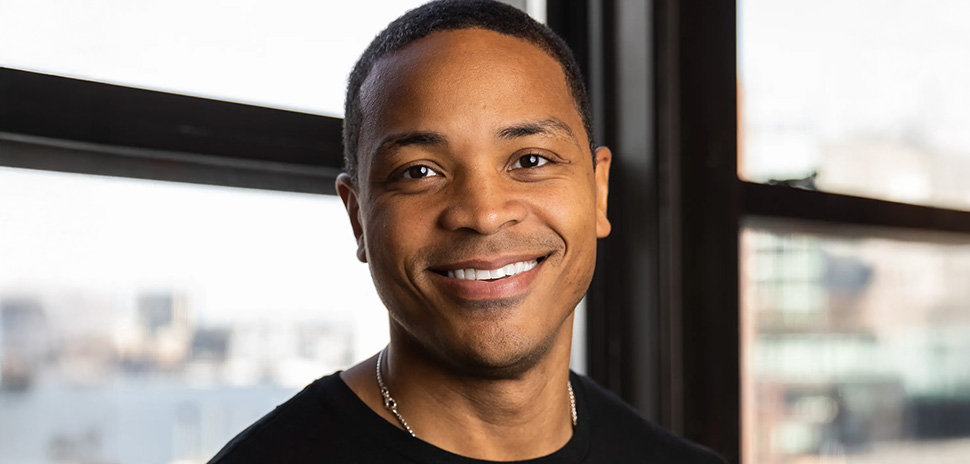

A New York native, Cusick has made Dallas his home for the last four years. He received his master’s degree in fine arts at Southern Methodist University back in 2013 and never left. His work is exhibited locally by the Holly Johnson Gallery in Dallas.

He recently took time to talk with Dallas Innovates about how his art has developed over the last 15 years, his impression of the Dallas art scene, and his future artistic endeavors.

How would you define yourself as an artist?

As someone who has committed about 15 years to [a] body of work with maps. It’s given me a platform and a unique expression that’s recognizable to where people can associate the work with me.

As someone who has committed about 15 years to [a] body of work with maps. It’s given me a platform and a unique expression that’s recognizable to where people can associate the work with me.

That’s a gift and a very fortunate thing to have, but as an artist right now I’m in a transition period. I’m looking to find all the things I’ve learned from working with maps the last 15 years to take it, distill it, and make it into something new.

I am determined to integrate science, art, and — for lack of a better word — the human condition.

I want to keep the essentials. I want to use those maps, instead of just grabbing any map because of the way it looks.

It has to do with the words. I’ve been painting with maps for the last 15 years. I gave up paints in 2002. Now, I want to create a new type of cartography.

So, how do I see myself as an artist? I’m determined to integrate science, art — and for lack of a better word — the human condition.

When did you start creating your map art, and what was the inspiration?

I was a painter. I was frustrated with the association that paint brought with it as a medium of fine art. My interests were much broader than just art. I had a lot of interest in history, science, information graphing, visual information graphing, graphic design, storytelling, narratives — all that stuff.

With the paint, I felt there were third-grade painters out there. Then, there were painters who could use paint and create something visually stimulating and beautiful. I was much more concerned with the content. If I could find a material that already had embedded in it the contents I was interested in, and use it like paint, I could continue to make pictures, but there would be an added dimension.

The real back story to all this was that my grandmother was a hoarder. Like, really bad … [she] would’ve been on that show if she had the chance.

When she died, I was the one who went to open up her door. … My dad hadn’t been in there in years. I opened it up, and it was “de de de,” like that Pyscho moment. There were stacks of pizza boxes, and there was a trail about one foot wide that went from the door to the kitchen to the bathroom and to the bedroom. My grandfather had abandoned her, and she had been in the hospital but she had lived there alone for awhile. I had no idea.

An artist is someone who needs those things, [needs] to have them near because they generate good energy, creativity, and ideas.

As I started cleaning, I got one of those enormous dumpsters. When I got down to the bottom I started finding the most amazing things — part of those things were these incredible collections of old maps. Nobody wanted them, so I took them home and they sat in my studio for awhile. At that same time I started getting frustrated with paint and the maps were just sitting in the corner. I just picked it up.

You get into things, and you just have to have it around — that’s an artist. An artist is someone who needs those things, [needs] to have them near because they generate good energy, creativity, and ideas. That’s how I am.

I have things in boxes and things I have never used that I keep around, because I know one day I will use it. The maps sat there for about a year, She passed away in 2001, and finally, I picked one up.

[There] was a picture of Bonnie [Parker], from Bonnie and Clyde. It was pretty gruesome, because it was from the autopsy. I took the map of Dallas and put it right on her cheek where one of the big gun wounds would be. Boom — it was just like that. After that, I told myself my next piece was going to be all maps.

Tell me about your artistic process. Does technology come into your process at all?

The technology started in my process when I had an idea for film. I had taken film classes in Cooper Union (college), but [Final Cut Pro] had just become available on computers.

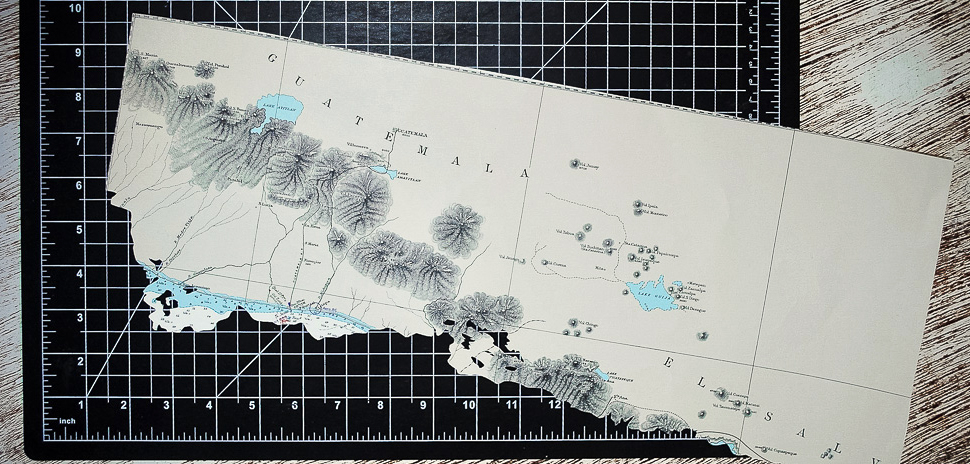

I did a disappearing act for a year and watched every single action movie I could find and downloaded only the car chase scenes. Then, I cut and spliced them all together — 500 movies — and created a continuous chase scene. That’s where the idea of splicing maps came from. Not the inlaying, but taking disjointed maps from different time periods and then putting them together and creating a new timeline that almost hops through worm holes.

How do you intend for the viewer to interact with your map artwork?

To read it like a book — that is my biggest goal.

I want my work to be a source of information that generates thoughts and ideas, which in the end enriches the art.

I go to a book store, and I’m one of those people who see a beautiful book cover and I pick it up. I may not always buy it, but I want it both ways: I want to have a beautiful book cover that draws people in, and then they open it up and can’t put it down. I want to create a painting that will engage [people] like a book would.

Whenever I have a show, and I see someone standing with one of my paintings for half an hour, that is one of the most rewarding experiences for me. They step back, look at the words and remember things. Then they come up to me and ask, “I noticed you put such and such in there, why did you do that?” And I tell them because there is a reason. I want my work to be a source of information that generates thoughts and ideas, which in the end enriches the art.

Your source materials come from an expansive archive you have collected over the years. How do you choose which ones to use in a piece?

I will find good resources. I read books, and I take notes — mark down chronologies, take down places and time periods. After that, I will know if I have the right maps. I have a very good memory of what maps I have. (Finding them might take a while though.)

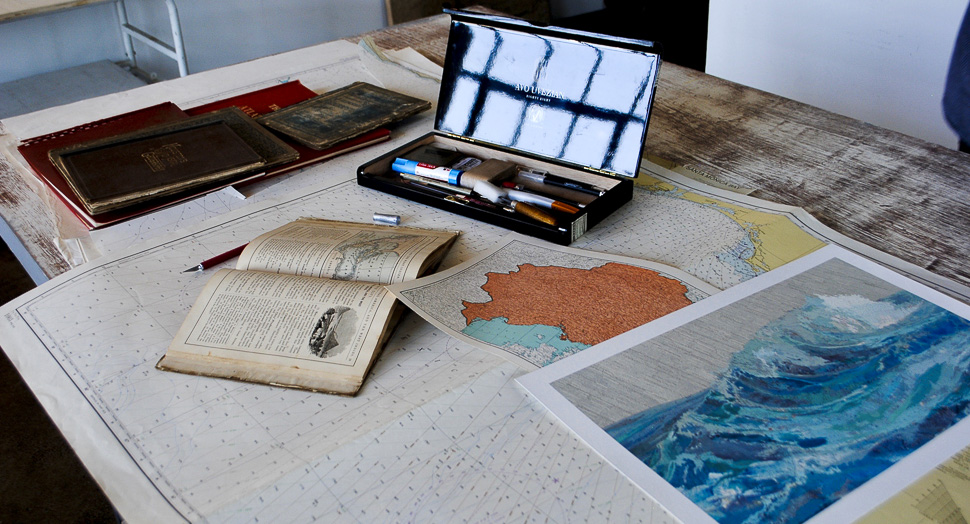

I compile them all together, and like a painter, I will create a palette.

I compile them all together, and like a painter, I will create a palette. I organize them into warms and cools — different values. Then, I will start painting with them.

After that, I look at my subject and say, “Okay, well, her skin is going to be this tone.” So, I will pull that tone from my painter’s palette of maps.

Has living in the Dallas art scene affected the way you work or the type of work you do?

I got my master’s [degree] at SMU and did that because I knew I needed something to fall back on. I met so many wonderful teachers and artists there.

In terms of Dallas itself, there are so many amazing artists here, but it frustrates me because there are so many serious collectors here [too]. I feel as though they don’t give local art the attention — or investment — it deserves.

What I would like to see happen in Dallas is collectors helping Dallas grow as a strong independent art center, even internationally.

There are two types of collectors: those who buy and invest, and those who just buy because they like it. I’m in a weird place because my prices are midrange — where they are too expensive just to buy if they like it, unless they really, really like it. Then, if they are really wealthy they think, “How much can I get for this at auction?” The thing about the art world is that the collector is the shark. The museums even cater to the collectors.

What I would like to see happen in Dallas is collectors helping Dallas grow as a strong independent art center, even internationally. … people need to invest in Dallas artists. All the elements are here.

Anything else readers should know about you or your upcoming artistic endeavors?

Let’s put it this way, I have purposely gotten myself lost in the woods, but I have left myself a trail of breadcrumbs.

The Native American tribe, Sioux, would do this thing where they would go up the mountain when they were going through bad times or felt bad spirits. They couldn’t sleep, eat, or seek shelter from storms. They had to stay in the same position for six days. They would come down from the mountain almost at death’s door. But, when they were on top of the mountain overlooking nature they would say,”I don’t know where I am going, but when I get down this mountain I will know.” That is how I feel right now, I am coming back down the mountain, and I’m bringing some new stuff with me.

PHOTO GALLERY

Photos by Meredith Mills

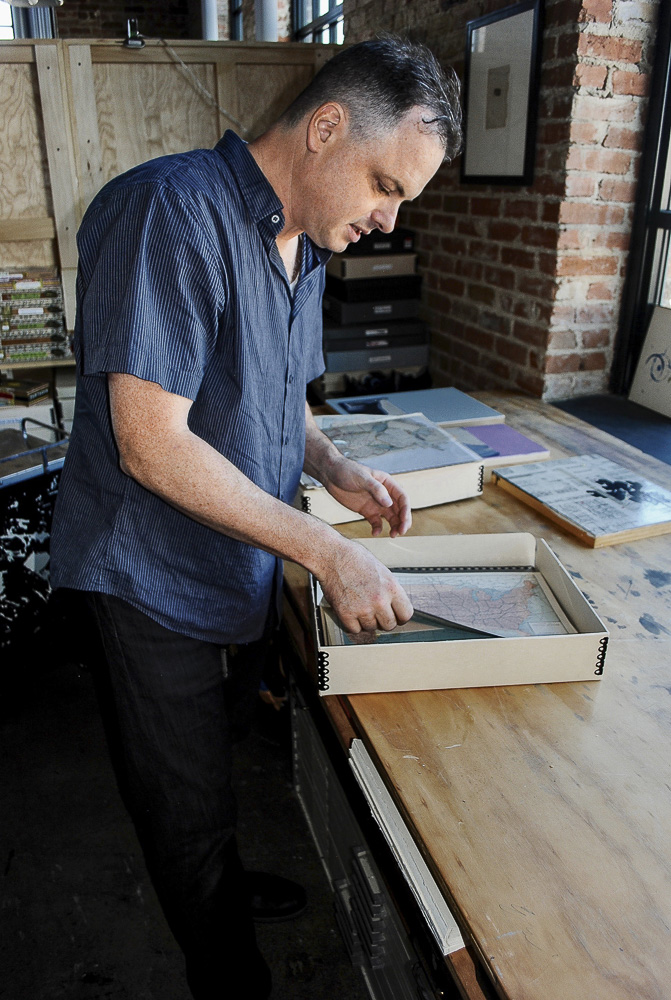

The artist in his studio

The artist at work

Dallas Innovates, every day

One quick signup, and you’ll be on the list.