Through much of 2020, the bells didn’t ring. School was out, virtual learning was in. As districts look toward a new normal, architects are using bigger-picture thinking to build schools that can create transformational change. Designing the future of education, says Leonardo González Sangri of HKS, is all about equity, community, adaptability, health—and keeping an open mind.

Here’s what the director of education at HKS had to say.

What opportunities and challenges do you see in educational architecture for the coming year?

What opportunities and challenges do you see in educational architecture for the coming year?

First and foremost, I see a chance to deliver equity in access to opportunity. How can school architecture influence equitable access to prosperity? What messages are being sent to students by virtue of the space we build for them? What message is sent by virtue of how we engage them in the design process? For us, it means addressing design problems with an open mind, without a pre-conceived idea. To listen intently, and let the conversation uncover the solution. Architecture that responds to the true needs of the community in support of the institutional goals can deliver transformational space.

The challenges ahead in education are, as in most industries and realms, great ones, and go well beyond architecture. However, to answer the question directly, the primary challenge in educational architecture today centers around resilience. The current emergency has highlighted the need for additional considerations in the design of educational facilities that revolve around adaptability, flexibility, and most importantly, health and health safety. The pandemic has also shined a light on the importance of life-cycle analysis to understand building systems and their impact on health to focus on long-term benefits in balance of initial capital costs.

The challenge is to design buildings that can perform to high, measurable standards of performance, and then measure them to ensure they continually do so. Healthy material choice, more efficient/higher-rated building systems (HVAC, plumbing, etc), and strategies to improve indoor conditions should all be evaluated—along with desired outcomes of health and well-being—and become part of the stated objectives of building performance. We have the technology to monitor the outcomes, so the architecture needs to evolve to take advantage of the technology in the service of users.

In terms of opportunities, the current pandemic can be viewed and ultimately leveraged as a tremendous opportunity to improve upon everything—including education and the way we design buildings for education. As the pillars of our communities, educational institutions are in the unique position to be agents of transformational change.

Additionally, I see an opportunity to design for emotional health and well-being. In the last decade, we’ve learned of the alarming prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress reported among students of all ages. We know from research that there are ways to use design to create spaces that help reduce these conditions and increase happiness in users. For us, that means thoughtful consideration for all users—the entire spectrum—will derive in a truly inclusive environment for the benefit of learning for all.

Finally, I see a chance to engage our clients in a deeper, more meaningful way, to help them uncover solutions that might be possible with bigger-picture thinking. As architects and designers, we’re trained to problem solve. We have the ability to make connections between seemingly unrelated notions to uncover value. We work rigorously to understand all our client’s challenges and limitations, to question assumptions, and to challenge the status quo, so we can deliver solutions that had not been imagined.

Has the pandemic impacted the way you design schools?

The pandemic is changing how we approach design, but it hasn’t fully played out. As I mentioned in the opportunities above, there are many ways in which our process has shifted to promote inclusivity and human-centered design.

Our design process has been augmented using tools we’ve developed to infuse it with empathic decision making. One good example is the Persona Mapping tool. As humans, it is at times difficult to remain objective or avoid projecting our own experiences onto our design decisions. Through the development of project personas, we’re able to create a framework that can inform our decision-making process with relevant information about the project’s users. This allows our design teams to have meaningful conversations with our clients about their assumptions and make decisions based on research. Recently our team at UCSD reevaluated the assumption of a cafeteria need for a student-life project. By basing their work on research that uncovered a different need, the design solution became a marketplace, which enhanced the project in a dramatic way, without increasing the project budget.

Additionally, we employ the AIA’s Framework for Design Excellence to identify ways in which our clients’ goals can go beyond the project itself to build healthier, more resilient communities. Through this process, we define design outcomes that elevate the project to be a key contributor to its own ecosystem. As a firm, we’re looking at ways to think about our work and its influence in our communities and their ability to bounce back from crises. Recently, our research group developed the Community Bloc Framework for Healthy and Pandemic-Resilient Communities. Leaning on evidence from urban studies as well as infection prevention, we explore how to design the ability to transform an environment from times of health to times for weathering a health crisis, in a way that cultivates human, environmental, and fiscal health.

What features will be most important in schools of the future?

Resilience, sustainability, health, and technology.

Designing for resilience is of paramount importance today and into the future. As we move into a future riddled with great challenges, our built environment can play a big role in building resilience in support of our communities. Our schools of the future can play a bigger role in the success of our communities, leveraging interdependent programs, or functions that consider inter-generational and inclusive environments. By thoughtfully designing for flexibility and adaptability, with relevance to place and in consideration of human needs, our buildings can help us manage crises and build community. This adaptability will manifest itself through rapid re-purposing of spaces, flexible design, and more agile infrastructures.

Another recurring topic here is health, both from the perspective of our physical and mental health, but also from the notion of our health safety. These topics will become primary concerns of educational facilities as we all work to get back to normalcy and learn to live with the fear of pandemics.

Holistic sustainability goes hand-in-hand with resilience. Baked into our ethos is the notion of holistic sustainability, which includes environmental, social, and economic sustainability. It’s at the intersection of all three that true sustainability emerges. We develop a rigorous approach that considers all three as the basis to uncover value that goes beyond the project site itself and adds meaningfully to its community.

Finally, technology will inevitably be a key feature on many fronts. Depending on how it’s developed, it can become a transformational force in how we understand the basic building blocks of a school. How and where we learn will be deeply impacted by technology. Will it render the classroom obsolete? Is the development of AI going to re-shape how we measure attainment in students and therefore re-shape how and what we teach? Will we adopt a model of technology that enables us to deliver true equity in education? Will we overcome the challenges of access that our underserved communities struggle with today?

What current and upcoming projects are you excited about?

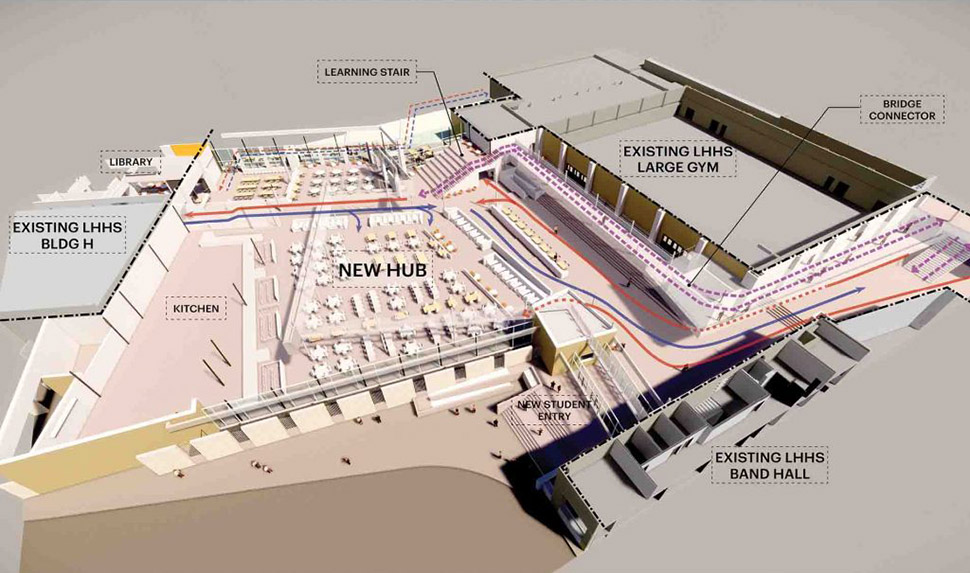

In the K-12 arena, we’re very excited about the upcoming opening of our renovation of Lake Highlands High School in Richardson ISD. This project is a great example of a user-centered approach where we used the district’s inclusive design process to uncover tremendous value for LHHS students and faculty. What began as a classroom addition to connecting two existing buildings became a new school HUB: a flexible space that serves the school’s needs for the cafeteria, library, and informal learning opportunities—while creating a connection between the buildings filled with natural light and visual and physical access to nature. Through creative thinking, we were able to deliver the entire project, including the originally programmed additional classrooms, with no additional money requested from the board. By digging deep into what the school needed, we uncovered a solution that will impact the health of the students in a transformational way.

In higher education, we’re looking forward to the imminent opening of our North Torrey Pines Living and Learning Community at the University of California in San Diego. Here, we employed our human-centered design process to deliver a solution deeply rooted in research. The building recently went through an analysis to evaluate resilience and adaptability as the university considered their back-to-school plans. Our client was pleasantly surprised at how well the project’s design features flexed in support of their plans, especially considering that it was designed well before the pandemic.

A version of this story first published in the Fall 2020 edition of the Dallas-Fort Worth Real Estate Review.

Read the digital edition of Dallas Innovates’ sister publication, the Real Estate Review, on Issuu.

The Dallas-Fort Worth Real Estate Review is published quarterly.

Sign up for the digital alert here.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.