Researchers at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas have found that a newly discovered “timekeeper” for fighting infections dramatically shapes the body’s immune defenses and offers insight as to why antiviral T cell response varies throughout the day.

The findings, published in Science Advances, could lead to new strategies for treating infections, using immunotherapies to combat cancer, and limiting the effects of body clock disruptors such as jet lag and shift work, according to UT Southwestern.

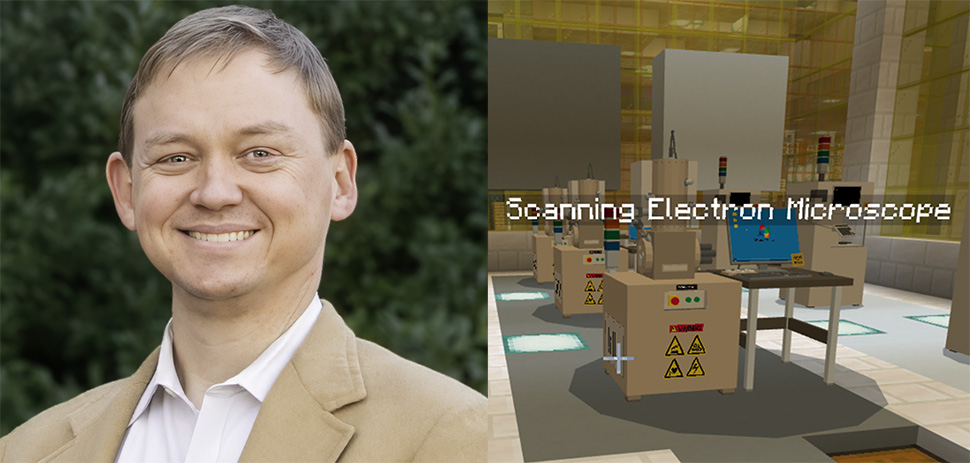

“The adrenaline receptor sets the internal clock of virus-specific T cells, which regulates how well they respond to viral infections at different times of the day,” said David Farrar, associate professor of immunology and molecular biology at UT Southwestern, who co-led the study with instructor of immunology Drashya Sharma.

The researchers discovered that the protein, which binds to adrenaline, appears to act as a timekeeper for T cells’ infection-fighting function. The pathway suppresses inflammation while increasing vulnerability to disease, UT Southwestern said.

The discovery could help explain why individuals might be more susceptible to some infections or experience more severe symptoms at various times during a 24-hour period.

The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Beecherl Endowment of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

How circadian rhythm impacts the immune system

According to UTSW, most organisms have biological functions that cycle on a 24-hour time frame, a phenomenon known as circadian rhythm. For humans and many other mammals, light sets these cycles by programming a region of the brain that sends chemical signals throughout the body to synchronize the circadian clocks in cells, tissues, and organs.

Scientists have long known the immune system functions on its own daily cycle—vaccines tend to elicit a greater immune response when given in the morning than at night—but it has not been known which chemical signals regulate its circadian clock.

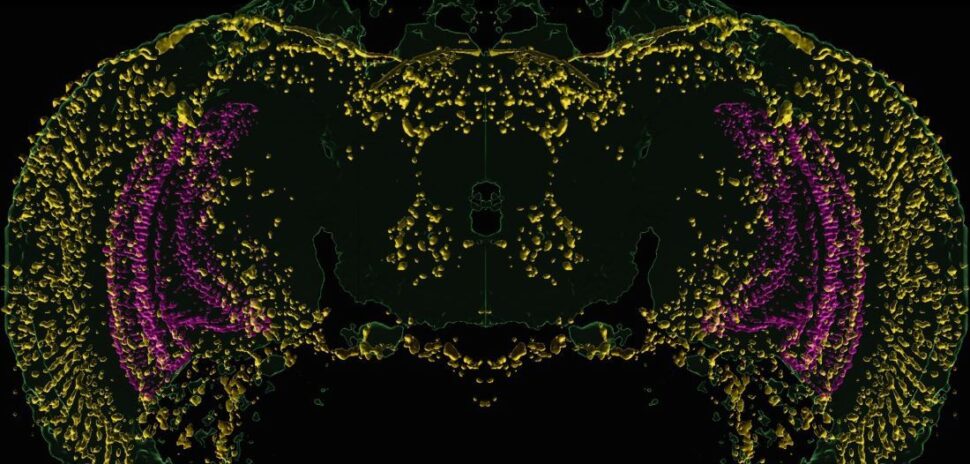

UT Southwestern scientists plotted T cells on a graph that provides the backdrop for a clock, showing that circadian rhythms regulate these immune cells’ response to viral infection via the adrenaline receptor based on the time of day.

The study found that T cells respond rapidly to infection by developing into unique populations of virus-killing subtypes.

How they made the discovery

Farrar, Sharma and their colleagues found that deleting ADRB2 had an inconsistent effect on these circadian clock genes. While some lost their rhythmic expression, others adopted abnormal rhythms, either shifting when they were normally expressed within a 24-hour cycle or cycling outside a 24-hour period.

Next, UT Southwestern tested healthy, normal mice and others genetically altered to remove ADRB2 from their T cells by infecting them with vesicular stomatitis virus, a common pathogen for this species. T cells of the mice with ADRB2 proliferated and differentiated into various subsets, as typically happens after exposure to bacterial and viral pathogens. T cells of the mice lacking ADRB2 had reduced proliferation and differentiation.

A subset particularly affected in the altered mice was memory T cells, which are targeted by vaccines, according to UT Southwestern. Those cells stick around after infection, preserving a cellular memory of the pathogen so they can launch a new attack upon a future exposure to the same pathogen.

The adrenaline connection

Farrar and Sharma explained that adrenaline produced by brain cells rises upon waking and falls at bedtime, a cycle that’s the opposite of immune activity.

They said that because some circadian clock genes in T cells continue to cycle even in the absence of ADRB2, adrenaline is probably just one of several chemical signals that direct circadian rhythms in T cells.

Future research in the Farrar Lab will focus on identifying other cycle-setting chemicals in these immune cells as well as how they affect T cell response to various pathogens at different times of the day, according to UT Southwestern.

Other researchers who contributed to this study include Kira Kohlbach, research assistant II, and Robert Maples, graduate student researcher.

Don’t miss what’s next. Subscribe to Dallas Innovates.

Track Dallas-Fort Worth’s business and innovation landscape with our curated news in your inbox Tuesday-Thursday.