It’s been a challenging environment for startups seeking private market capital, with closings, returns, and valuations generally predicted to continue down this year. Nonetheless, biotech ventures can employ certain strategies to forge rewarding financial partnerships with alternative investors and family offices in particular.

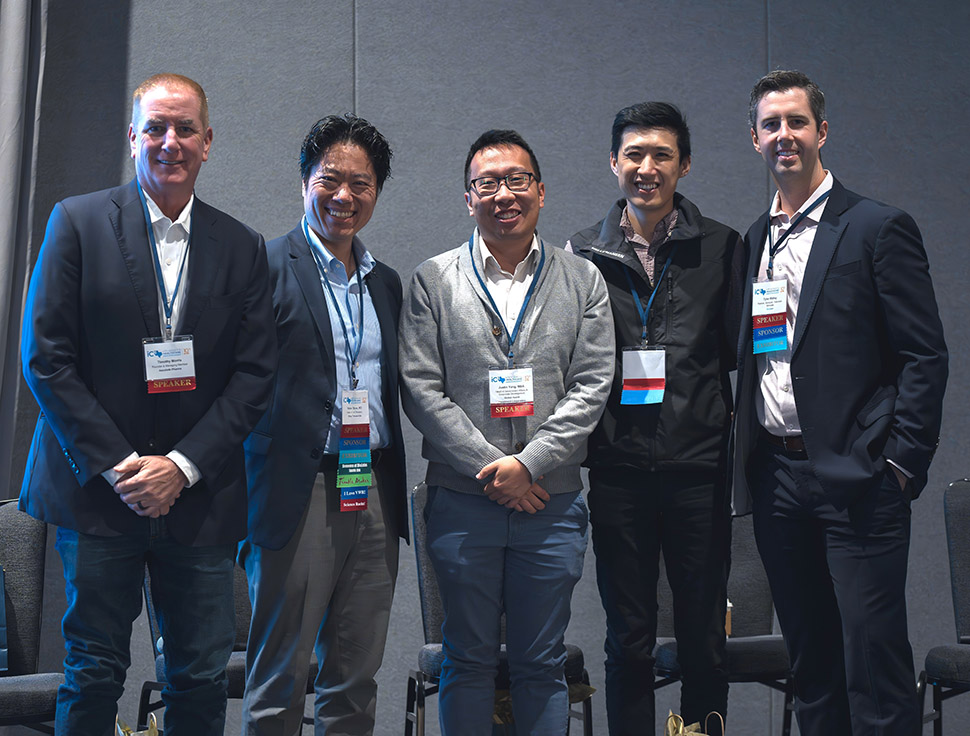

That was the gist of a panel discussion titled “Lessons Learned When Engaging Family Offices and Alternative Investors” at BioNTX’s recent 10th annual iC3 Summit at the Loews Arlington Convention Center.

Members of the panel were Yizhen Dong, a partner at Echo Investment Capital; Timothy Morris, founder and managing member, Aacolade Pharma; Vic Stone, M.D., head of cell therapies, Alloy Therapeutics; and Justin Yang, head of government affairs and corporate development at Global Health Investment Corp. (GHIC).

From left: Timothy Morris of Aacolade Pharma, Vic Stone of Alloy Therapeutics, Justin Yang of GHIC, Yizhen Dong of Echo Investment Capital, and Weaver’s Tyler Ridley. [Photo: BioNTX]

‘Lessons Learned’ Discussion

The discussion was moderated by Tyler Ridley, partner, valuations, and head of life sciences at Weaver, who began by asking the panelists what role non-institutional capital, like family office funding, plays within the private investment ecosystem.

Timothy Morris: It’s a really great source of capital. And while it may be a really great source, a lot of that non-institutional wealth was generated from other than pharmaceuticals, other than biotech. So, that’s a challenge. But it’s a good source. it’s relatively patient money. It probably takes longer to get and takes more education, but it’s definitely an alternative. I guess the one thing I would say is that, usually there’s a personal reason for investing—whether it’s the Michael J Fox Foundation [for Parkinson’s disease], or folks who have had Duchenne muscular dystrophy in their lives, or there’s some oncology player. If you can find somebody who shares a passion for what you’re trying to do for patients, you have a much better shot.

Vic Stone: When I think about institutional investors, the check sizes tend to be a lot larger. But at the same time, they have contractual obligations—you know, an investment with patents must have this type of profile, this kind of track record, everything needs to fit into a specific box. And so, whenever you move outside that, I think that’s when non-institutional money becomes really critical. Biotech is a situation that requires $50 million to $100 million to get a drug to phase 1 or 2, and a lot of times there’s a lot of messiness that happens that we all deal with. So, I think non-institutional money in the context of therapeutics is absolutely critical.

Tyler Ridley: Since biotech clinical studies take a lot of capital, and therefore institutional dollars are needed, do you see non-institutional funding as more of a ‘kindling’ for early-stage, and then you have to find more institutional dollars at a later stage? Or is non-institutional funding sufficient for a biotech company?

Stone: Over the past couple of decades, the time and cost horizons of getting something from academic science into something that fits the institutional investment profile have improved significantly. Back in the day, I think it was a lot harder. So, there’s more of an opportunity now for these single and multifamily offices to make an impact in the space.

Justin Yang: I agree that the cost of [institutional] capital is significantly lower than maybe 10 years ago. A large number of case studies show this. The most famous one would be the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, which supported and developed the cystic fibrosis drug Trikafta [with] Vertex Pharmaceuticals. The other more recent one would be the Mitokinin story from Abbvie, which just acquired the company and a Parkinson’s drug last year, following grant support from the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Abbvie took that on and developed the drug further, after acquiring the preclinical asset for $120 million upfront. I think the total economics were over $600 million. And the company itself had only raised, I think, less than $20 million. I think there’s a way to build a company smart, leveraging capital and partnerships.

From left, family office panelists Morris, Stone, and Yang at the recent BioNTX Summit in Arlington. [Photo: BioNTX]

Ridley: Thinking about getting ‘smart’ capital, like you mentioned, you want to be careful with what kind of investors you bring in because, in the wrong scenario, your investors can actually be a pretty significant liability. So, how do you go about building or gaining smart capital—especially within the family office space, where there could be a large variance in the degree of sophistication?

Morris: I think one thing that’s important in dealing with less sophisticated investors is: a lot of education. There are two points: They need to agree to your mission. And, especially for folks who may not fully understand pharmaceuticals, drug development, the FDA, pricing, and reimbursements, you need to make sure you spend time and educate the folks who are making the investment decision. That’s really a challenge in the family office, where you might be dealing with someone who’s more administrative or more of an investment manager. Ultimately, at least in my experience, the family needs to make the decision, and sometimes the family has to be unanimous on it. Make sure they have prior investments in pharmaceuticals and understand biotech, and give them examples, case studies. Tell them how much it costs, tell them how long it takes, tell them you may not ever make money. If they say, ‘Well, you know, when are you going to be profitable? How much income did you make last year?’ ‘None and never.’ So, start with that.

Stone: For a lot of this non-institutional money, it’s really the first check, right? So, when you get that million-dollar check from an office, there’s a lot of responsibility that goes along with it. As a first-time entrepreneur in that situation, I think there’s a certain discipline you want to have. ‘Hey, should I take this cash? Is it really going to get me to that necessary value inflection point? Is it not three or five [million] that I really need?’ And I think a lot of family offices that want to give that opportunity might blindly put in that one million, without really understanding that that mill is not sufficient to bridge to that inflection. So, I think there’s a lot of discipline that we as entrepreneurs need to have, to walk away.

Yang: Just like there are different profiles of institutional investors, there are different profiles in family offices, starting from the totally unsophisticated kind of family office that wants exposure in biotech and life science, to the person that made their money in a different field but wants to advance science in a good way. When you take this money, and if this person is going to get a board seat, or they’re going to become your ‘boss,’ you’re going to have to think about whether this is someone you can work with. Do they understand how they can be helpful? Are you comfortable guiding them in this relationship on this journey? Because ultimately, you’re going to have to live with that decision. Later on, if you have access to more capital and you have multiple choices, obviously you’re doing to pick a person that can benefit you in a significant way beyond writing checks.

Ridley: Are there any trends or indications that family offices are more eager these days to syndicate in deals?

Yizhen Dong: I work for a range of family offices in healthcare and life sciences, some less sophisticated than others. Syndication means their capital would be less at risk, because there’s more capital coming in. That’s kind of the framework that people will have when pitching to less sophisticated investors.

Ridley: It’s been noted that family offices are really intentional about creating protective barriers and layers, for many reasons. Can you guys talk about any successful strategies that potential entrepreneurs can use to respectfully penetrate those protective barriers?

Morris: I’ll give you an anecdote from one of the companies where I sit on the board. We have a product that’s going to be used by the military, but that also has a play with radiation therapy for solid tumors. So, we [went to] a family office that has a military background and also [has interests in] cancer supportive care—institutional hospitals and other places to go. We found they were big supporters of the Navy SEAL Foundation. We have a fair number of military folks within the company on our board, and they also were participating in and supportive of that foundation. So, find their charity—find out what they’re passionate about—and you have a chance to kind of get into their world a little bit.

Dong: On the family office side, the No. 1 way to get in is to know their portfolio companies. So, if you know any investment they’ve done, I would reach out to those portfolio companies, build relationships, and have them give you a way in. They could be your champion. It’s very effective.

Yang: I think what he said is so important. Just go to the website of an investment group that you want to raise money from, and go find their portfolio companies and contact the CEOs and founders that have received money, and then develop a relationship with them. That email intro into the firm is going to be significantly better than just going on LinkedIn and asking for a meeting.

Stone: A lot of first-time entrepreneurs believe that getting in front of that investor is the most valuable thing. And if they can only pitch, they’re going to get something done. But that’s not the way it works. There was a very driven first-time entrepreneur and we said, ‘Hey, look, quit using your time trying to get in front of investors. Instead, focus on finding other co-founders who are willing to join you on your bandwagon—especially those who’ve been a part of successful biotech exits.’ That individual went and emailed 30 people a week and ultimately came up with a really nice club of co-founders. Now he’s in front of multiple check writers.

Ridley: Does anything else stick out, once you’re in front of investors?

Stone: Most of us who’ve been out there investing all agree what a well-structured, well-shaped-out opportunity looks like at the seed-stage level, and so a key is really creating that FOMO. The idea that, ‘Here’s this [indispensable] thing; we have the fully stacked, most dominant team; oh, my God, this is it!’ How do you instill that FOMO, right? Then the pitch just becomes this really fun story to talk about that people are really drawn into. It takes a lot of work to put that together, but I think putting that work in is part of it.

Dong: When I think about raising capital from family offices, I almost stay away from the facts and really try to connect with them on that emotional level. Oftentimes I hear my colleagues say, ‘If we lose them at that emotional level in the first 10 minutes, we’re done.’ So, having that connection is important. Show them your passion.

Yang: With family offices and high-net-worth individuals, the traditional path in is, you get that connection and they send you to a third party—a gatekeeper who manages family offices, for example. Due diligence is done, and ‘now we’re in.’ There are also advisors who manage hundreds of offices, and they have a form you can fill out. And once you’re vetted and you get like a blue check mark that says you’re ready now to receive funds, then you can start looking at other offices within that network. It’s kind of a secret club, but, if you can get in there, you’ll have a better chance of receiving money.

Ridley: There are a number of potential snake oil salesmen out there, though. How do you deal with them?

Yang: I feel very strongly about two things on this topic: No. 1 is, never pay to play. I hate going to conferences where you have to pay to be introduced to people. That’s terrible. No. 2 is, like, crowdsource funding, which turns off most investors—or, having a third-party placement agent (that isn’t a bank) that promises to do things in exchange for a retainer. You may potentially get more meetings, but are they meetings you wouldn’t have gotten yourself?

Morris: I’m going to agree with you, because I get pitched by these guys all the time: ‘Please come present to our family office, or our group of family offices.’ It’s usually in some swanky hotel or some Florida location or something like that. I’m like, ‘Great.’ Then they say, ‘Oh, by the way, it’ll be $5,000’ that I have to pay to come and pitch. There’s hundreds of these guys out there. I’ve looked for some that are good, and none of them are. I apologize if one of you is in this room. But, please don’t take these poor peoples’ money!

“Don’t let your first meeting be the one where you ask for money,” said Timothy Morris of Aacolade Pharma. “You need to build a relationship with these folks,” From left, Morris, Vic Stone of Alloy Therapeutics, Justin Yang of GHIC, Yizhen Dong of Echo Investment Capital, and Weaver’s Tyler Ridley. [Photo: BioNTX]

Ridley: I’m a valuation partner, so I want to switch quickly to valuation and talk a little bit about the nitty-gritty of what we’re seeing. I know valuations are down. But I’m curious what you’re seeing in terms of terms, preferences, and warrants and so on that might be juicing the returns for folks.

Dong: I think liquidation preferences are more commonplace now, and ratchets are coming back as well, unfortunately for founders.

Yang: I would say the capital equity markets have largely corrected and bounced back and are now in a state of equilibrium. I would say that there’s still a huge lag in the private valuations that raised in 2021, 2022, maybe even 2019. That other shoe has yet to drop. There’s a lot of venture firms that are underwater on their investments that they’ve made. I think that if you have money right now as a venture firm and you’re deploying, I think it’s a great time. You set the terms, you’re getting the best deals, you’re really driving the best value. Being realistic, I think most existing investors on the boards of these companies and their portfolio are now more realistic about taking 20%, 50% cuts on their valuations at the next raise just to bring in that new investor. I think that’s realistic, and I would encourage anyone here who’s raising to have a realistic view on that with your companies.

Morris: My comment would be this on valuation: As a private company, sometimes you’re dealing with folks who aren’t as sophisticated, especially entrepreneurs or founders, who think that every round needs to be up. Guess what? Not every round needs to be up. And, oh, by the way, if you have a down round, you didn’t lose money, nor did your private shareholders. The public markets are really efficient. They tell you exactly what you’re worth. You might think your asset is worth $100 million, and the market’s telling you it’s worth 10. Guess what? It’s worth 10. So be realistic in your expectations. The other thing I will say on term sheets is, these guys listen. Carve out something for the management pool. These guys all want ratchets, they want reset, they want liquidation. Guess what? You’re a founder. You need a pool of capital, whether it’s options, restricted units—doesn’t matter. Talk to your accountant and figure out what that is. These guys will agree.

Ridley: I think we have maybe five minutes left, so does anything else important come to mind?

Yang: [Following up on the earlier discussion about connecting with family offices.] You’re almost always likely to get a meeting if you offer to meet them face-to-face, for a coffee, say. Just pick a date sometime in the future and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to be in town on such and such date’—whether or not you’re planning to be there until that meeting happens—and say, like, ‘Let’s grab coffee and give you an update on the company.’ This is a strategy. Ours is a relationship business, and we don’t do deals with people that we don’t know. At the end of the day, if I’m going to give you $10 million, $15 million, $20 million, do I trust that you’re going to do the right thing? One meeting in person equals 1,000 emails, right?

Morris: The one thing I would add is, Don’t let your first meeting be the one where you ask for money. You need to build a relationship with these folks. You don’t ever want that phone call to go, ‘It was nice to meet you and, by the way, how’s your money?’ It never works that way.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.