For six straight years, co-founder Kathleen Hildreth of Denton-based M1 Support Services has been named to the Forbes list of “America’s Richest Self-Made Women.” In 2024, the Army veteran’s estimated net worth was $670 million as M1—a national defense contractor focused on aviation maintenance—saw its revenue tick up to nearly $1 billion.

Hildreth’s success, and that of the company she helped start, can be explained by a willingness to go above and beyond.

Consider, for example, how M1 (short for “Mission First”) handled its aircraft maintenance contract at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls. Realizing the training base was “way behind” on its key major aircraft inspections, she says, M1 set out to make improvements. They included implementing paperless recordkeeping and hiring some experienced, recently retired people to expedite the inspection process. The moves, all accomplished within budget,“ allowed us to dig out of a hole that the Air Force was in,” Hildreth recalls.

An employee of M1 Support Services works on a U.S. Air Force T-38A Talon aircraft at Mountain Home Air Force Base in Idaho, in 2022. [Photo: Tech. Sgt. Betty R. Chevalier, U.S. Air Force]

By most accounts, M1’s is a different, “value-add” approach to aviation services—a highly competitive and regimented sector of government contracting whose providers typically go strictly by the book.

“We’ve said to customers, ‘Look, there’s some problems out here that need to be solved,’” says Hildreth, 63. “And even though it seems like it’s kind of a low-tech business, we’ve put in a lot of continuous improvement teams. We introduced some training—virtual reality and augmented reality training—that brought a little technology and a little process improvement that enabled us to give customers more for their money.”

Innovation like that is part of the M.O. at M1, a leading aviation-maintenance player that Hildreth and her business partner William Shelt founded in 2003. The company, whose work includes aircraft maintenance, training, and logistics support for fixed- and rotary-wing military aircraft and aviation programs, now has more than 5,000 employees. Besides the U.S. Air Force, its customers have included the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, Veterans Administration, General Services Administration, Drug Enforcement Administration, NASA, and the Federal Aviation Administration.

Last May a controlling interest in M1 was sold for an undisclosed sum to Cerberus Capital, a New York-based private equity firm with about $65 billion in assets. Cerberus brought in George Krivo, a former CEO of DynCorp International, to be M1’s chief executive. “We felt like they had the knowledge and experience to keep the momentum going for the company,” Hildreth says.

She and Shelt are still investors in M1—Hildreth owns 10%—and both are active members of its board of directors.

An interest in aviation since childhood

M1’s “momentum” is due in part to Hildreth herself.

A native of Trenton, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, she says she spent time flying as a youngster in a small Cessna 172 with her parents, both of whom were licensed pilots.

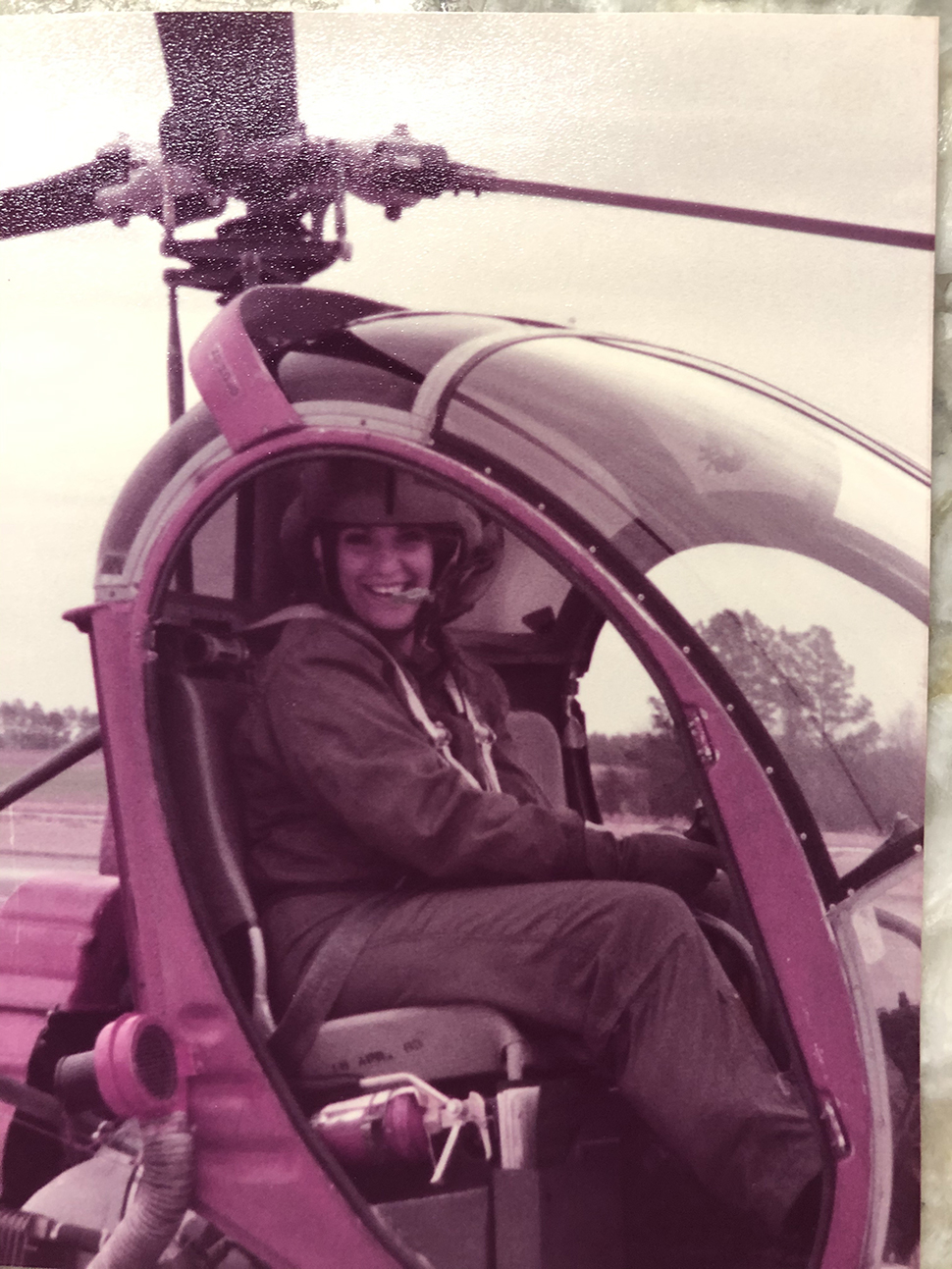

Hildreth begins learning to fly helicopters in 1984 in a TH-55 training craft at Fort Novosel (then called Fort Rucker) in Alabama. [Photo: M1 Support Services]

That piqued her interest in aviation, which she pursued during studies at the United States Military Academy at West Point. After graduating in 1983, she was commissioned into the U.S. Army’s aviation branch and, for five years, flew helicopters—Hueys and Blackhawks—and served as a maintenance test pilot.

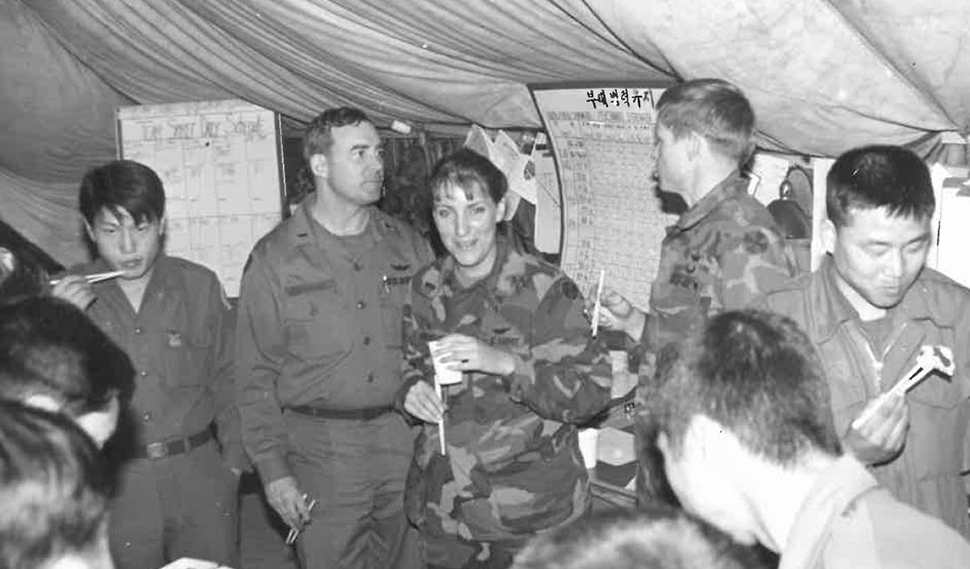

Outside Seoul, South Korea, Hildreth enjoys a food break at the tactical operations center following a joint U.S.-South Korean military training exercise in 1984. [Photo: M1 Support Services]

In 1988 she left the Army as a service-disabled veteran and went to work for a series of defense contractors, including GE, Lockheed Martin, and DynCorp.

She was with DynCorp from 1991 to 2003—the last four years in Fort Worth—and eventually became its vice president of business development, tasked with pursuing aerospace and defense contracts worldwide.

But after interacting with a number of successful, specialized small-business subcontractors—women-owned and veteran-owned, for example—Hildreth says she realized she was “more qualified and probably more well-equipped” to start a business than some of them.

So, that’s just what she did.

“I went out without any contracts or work, and I approached large businesses, primarily in the same way small businesses had approached me, and asked to be a subcontractor, help them win business, because I knew a lot about marketing and business development in the government contracting space,” Hildreth says. “In six months to the day after I left my job at DynCorp, I had my first subcontract.”

After its first full year in business, M1 had a little more than $1 million in revenue, Hildreth says. By year 10, it was generating about $1 million a day. By year 15, it was bringing in $2 million daily.

The growth all came organically, she says, rather than through acquisitions.

At Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, Georgia, in 1988, Hildreth accepts an award of excellence on behalf of her unit from Maj. Gen. Andy Cooley. [Photo: M1 Support Services]

‘You can grow things as big as you want’

In addition to making the Forbes “Richest Self-Made Women” list—the first military veteran to do so—Hildreth was named to the magazine’s list of “50 Over 50” in the Innovation Category in 2023. She’s been on the board of the Wounded Warrior Project since 2020 and, last year, was selected as a Distinguished Graduate of the United States Military Academy.

In November she also was inducted into the Texas Business Hall of Fame. Introducing Hildreth at the HOF induction dinner in Dallas in November, Preston “Pete” Geren III—a former Texas congressman and Secretary of the Army from 2007-2009—said Hildreth’s life and career “epitomize ‘can-do.’ ”

During her remarks at the dinner, Hildreth said M1’s “secret sauce” has been talented people, a shared culture, a shared vision of success—and grit. “If you surround yourself with the right people, build a culture that supports your mission, and never let setbacks define you, there’s nothing you can’t achieve,” she said.

In an interview later, she offered some additional advice for entrepreneurs:

“The other thing people need to do is not limit themselves to what they think is ‘big’ or ‘next.’ Because it’s my belief that you can grow things as big as you want. You just need to put the right work in. A lot of people told us we were too small, so they weren’t going to award us a contract. And we just said, ‘You know, I’ll show you.’ And we went out and just worked our tails off and were successful.”

Hildreth returns to her alma mater in 2022 to speak to the Corbin Forum, a leadership group of mainly women cadets, at the United States Military Academy at West Point, [Photo: M1 Support Services]

But, as a woman in the military and the defense sector, both traditionally male-dominated, did she ever feel at a disadvantage? Even last year only about 8% of U.S. military pilots were female, according to reports, and women accounted for just 25% of the workforces at the top five defense contractors.

“I was well-prepared, very experienced, and frequently looked to as the most knowledgeable person in the room. So, for me, it wasn’t an impediment,” Hildreth says. “I tell every young woman or girl that I talk to, ‘Don’t go and be the best girl or woman. Go be the best at what you do.’ When you’re the best at what you do in the classroom, or on the field, or in your career, then nobody’s going to question, ‘Why is a woman here?’ Because they know you’re competent. And I think competence breeds confidence.”

It sure did in Kathleen Hildreth, anyway.

Don’t miss what’s next. Subscribe to Dallas Innovates.

Track Dallas-Fort Worth’s business and innovation landscape with our curated news in your inbox Tuesday-Thursday.