Private investments in environmentally-friendly energy inventions may be poised for a rebound — and North Texas is helping lead the charge, according to panelists at a conference last week.

Known as “clean technologies,” or clean tech, the field wasn’t developed enough to deliver strong financial returns quickly when venture capitalists poured large sums of money into it late in the last decade, speakers said April 19 at the E-Capital Summit, held at Dallas’ Fair Park.

The conference was part of EarthX, an annual gathering in Dallas centering on ways of improving the environment.

“Clean tech in 2007 was too early and had too big of a chasm,” said Victor Liu, president of Hunt Energy Enterprises, LLC, an incubator in the Dallas-based oil and gas giant for new ventures in all areas of the power industry, including green-based systems.

“We care about being sustainable.”

Victor Liu

Of the $2.7 billion in revenue that Forbes estimates the parent of Liu’s unit, Hunt Consolidated, brought in during 2016, the largest chunk came from oil and gas.

But Liu’s group is investing in promising technologies such as solar cells, partly because the family that owns and runs the business realizes that fossil fuels are a finite resource.

“If we don’t pay attention to renewables, that will impact the company,” Liu told the E-Capital audience during a panel about families and foundations investing in clean tech. “We care about being sustainable.”

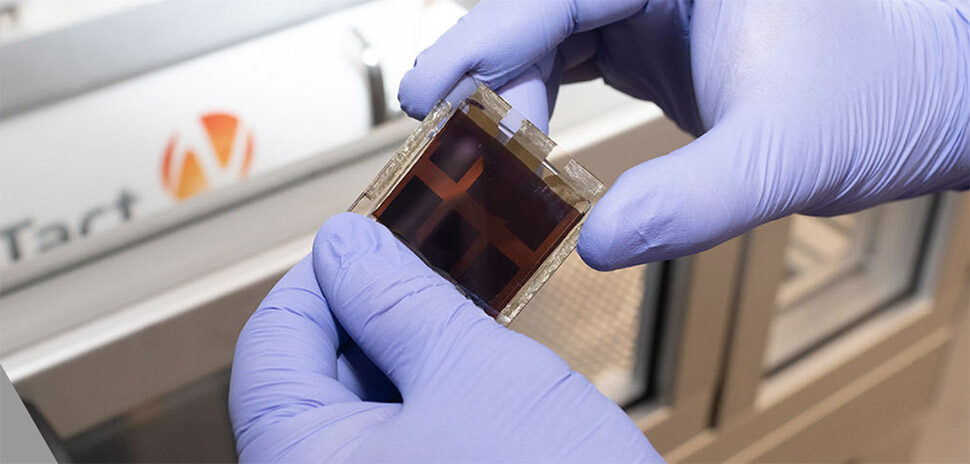

Among Liu’s stable of ventures is HEE Solar, LLC, to which Hunt Energy Enterprises has assigned, or transferred, ownership of at least four patents, records show.

The chief technology officer of HEE Solar, Michael Irwin, is listed as an inventor on each of those patents, as well as on at least five others that Liu’s unit owns, records say.

The patents center primarily on methods for making solar cells that contain pervoskites, a group of compounds that are cheap and easy to use for manufacturing.

Pervoskites last year could turn 22 percent of sunlight into energy, efficiency that rivals that of silicon, which is used to absorb light in more than 90 percent of the world’s solar cells, according to Science News.

Building solar panels with crystalline silicon entails heating materials to up to 2,000 degrees Celsius, a costly, difficult requirement.

Perovskite crystals, on the other hand, form at temperatures below 200 degrees, Science News reported.

Hunt has a development partner for HEE’s technologies, Liu said. “Our goal is that [commercialization] activities would take place this year.”

EarthX Vice President Matt Myers (far right) moderates a panel about new investment tools and business models during the E-Capital Summit Thursday. [Photo: Shay and Olive Photography]

COMBINING FOR-PROFIT, NONPROFIT FUNDS FOR CLEAN TECH

The North Texas area played a key role in a pioneering experiment in funding clean tech through combining philanthropy with for-profit investing, speakers at the subsequent E-Capital panel said April 19.

Quidnet Energy raised a combined $1 million seed round to test whether an old natural gas well about 80 miles southwest of Fort Worth could store energy that solar and wind power creates.

Loading the well in Erath County with water filled cracks and fissures of underground rocks. It also compressed those rocks, making them act like a large spring, Forbes has reported.

The North Texas area played a key role in a pioneering experiment in funding clean tech through combining philanthropy with for-profit investing.

Releasing the water spun a turbine generator, creating energy much like a waterwheel that turns from a river’s current.

The pilot test for Quidnet was so successful that it led to $17 million in funding for another half-dozen-plus proof-of-concept projects in clean tech, according to Sarah Kearney, founder and executive director of PRIME Coalition, a Boston-area nonprofit that cobbled the investments together.

“They’re the dream,” Kearney said of Quidnet during an E-Capital panel.

Initial investors in Quidnet, which is based in the San Francisco area, included a foundation run by actor Will Smith and his wife, Jada.

PRIME got the Internal Revenue Service’s green light to help nonprofits make equity or debt investments in deals that wouldn’t otherwise exist without charitable funds, Forbes has reported.

A for-profit opportunity of this type must be considered charitable by the IRS, Forbes noted.

Still, clean tech entrepreneurs face a shortage of capital for commercializing their ideas, according to Matt Myers, an EarthX vice president who helped create the E-Capital Summit and moderated the panel Kearney served on.

CHALLENGES EXIST, BUT OTHERS SAY ‘DISRUPTION’ IS HAPPENING

“What’s the difference between traditional and non-traditional capital sources?” Myers asked panelists.

A major challenge has been a gap between what clean tech could do versus what venture capitalists seek to invest in and what capital markets have demanded, according to Matt Price, managing director of partnerships at Cyclotron Road, a California fellowship program for entrepreneurial scientists.

Inventors in clean tech “don’t have a path for their ideas to change the world,” Price told the E-Capital crowd.

Because so many startups fail, venture capitalists seek returns of 10 to 30-fold-plus on each investment, published accounts say. As venture funds typically last 10 years, VCs usually invest during the first five years and cash in their chips on deals in the final five.

For now, clean tech generally doesn’t fit within those parameters, E-Capital panelists said.

“We believe the undercurrents of disruption are occurring.”

Victor Liu

Thus in the second, third, and fourth quarters of 2016, both Thompson Reuters and PricewaterhouseCoopers found $0 of initial investment from venture capitalists in clean tech companies, Kearney said.

“They stopped collecting that data from the ‘clean tech’ flag,” Kearney said. “Now they probably missed some things, especially from investors that are not compelled to share their data, like family offices. But $0 is symptomatic of a very serious problem.”

But as Liu of Hunt Energy Enterprises noted during the earlier panel, one person’s lemons are another’s lemonade.

“We believe the undercurrents of disruption are occurring,” he said. “The world is our lab.”