![]() Brain plasticity, or neuroplasticity, is the brain’s remarkable ability to change, adapt, and reorganize throughout our lives as we grow and learn. However, in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), learning results in the memories and sensory information surrounding a traumatic event permanently connecting to the emotional part of the brain that drives fear and anxiety, known as the fight-or-flight response.

Brain plasticity, or neuroplasticity, is the brain’s remarkable ability to change, adapt, and reorganize throughout our lives as we grow and learn. However, in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), learning results in the memories and sensory information surrounding a traumatic event permanently connecting to the emotional part of the brain that drives fear and anxiety, known as the fight-or-flight response.

PTSD is the result of enhanced learning during a traumatic event. During trauma, chemicals known as neuromodulators are released in the brain that can dramatically enhance learning. In PTSD, this learning is so strong that normal sounds, sights, and smells that were occurring during the trauma now trigger the emotional brain, resulting in a fight or flight response. The fight or flight response can be debilitating in severe PTSD, resulting in people disconnecting from the world to avoid triggering the response.

Think of your worst fear and the feelings that elicits. In PTSD, these feelings are even more severe and occur in everyday life as triggers, including smell or sound, remind an individual of their trauma—for example, for someone involved in a past accident, the smell of a diesel truck results in an uncontrollable fear of being hurt. Every time you drive — a seemingly normal activity — there is a chance you will experience that fear.

Hope on the horizon: Targeted Plasticity Therapy (TPT) for treatment-resistant PTSD

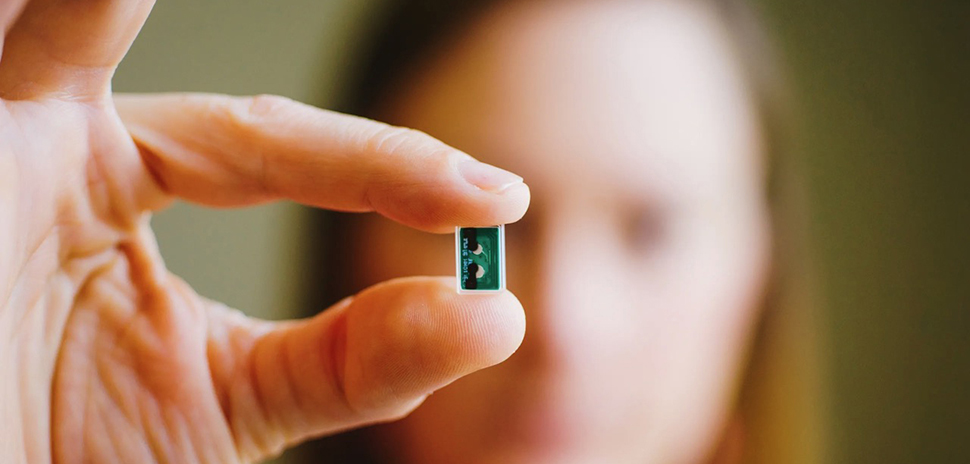

It seems like if PTSD is a learned response, it should be possible to unlearn this response. However, many people are treatment-resistant, and PTSD treatments fail. But hope is on the horizon. The Texas Biomedical Device Center team at The University of Texas at Dallas is working on innovative Targeted Plasticity Therapy (TPT) for treatment-resistant PTSD. This therapy involves implanting a minuscule device that stimulates the vagus nerve. This stimulation releases neuromodulators, which are chemicals that help the brain learn.

The goal is to use these neuromodulators to re-learn the traumatic memories that trigger the fight or flight response, teaching the brain that these memories are no longer a threat. Essentially, this process helps to separate the sensory and memory centers of the brain from the emotional parts responsible for PTSD.

Dr. Rennaker’s lab at the UT Dallas Bioengineering and Sciences Building. [Photo: UT Dallas]

The vagus nerve serves as your body’s superhighway

Your brain can be compared to a complex network of roads that can be rebuilt and rerouted as needed. The vagus nerve is like your body’s communication highway between your brain and many internal organs. It is crucial in regulating your “fight, flight, or freeze” response as well as your “rest and digest” state. As such, it may be the key to enhancing treatments for PTSD and other psychiatric and neurological conditions.

For many, PTSD is debilitating. Some people cannot leave their homes and often lose their social connections. TPT research aims to help patients fully reengage with the world around them. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with traditional therapies can double or even triple the effectiveness of results.

The gold standard for PTSD is prolonged-exposure therapy (PE), whereby an individual is gradually and repeatedly exposed to trauma-related memories. Instead of avoiding traumatic memories, the afflicted individual gradually confronts the trauma under the guidance of a trained therapist in a safe and calm environment. It’s like slowly moving your body from the shallow to the deep end of a swimming pool versus quickly diving into the deep end. The brain gradually learns that painful memories are no longer a threat.

The UT Dallas group working on experimental treatments for PTSD, Stroke, and Spinal Cord Injuries is the TxBDC team, which consists of three prominent faculty members (Dr. Robert Rennaker, Dr. Michael Kilgard, and Dr. Seth Hays), Chief Medical Officer Dr. Jane Wigginton, Director of Operations Amy Porter, 20 PhD students, and many other faculty members contributing to various pieces of their research.

TxBDC Team featured from left to right, Dr. Seth Hays, Amy Porter, Dr. Michael Kilgard, Dr. Robert Rennaker, and Dr. Jane Wigginton. [Photo: UT Dallas]

“It’s about the veterans”

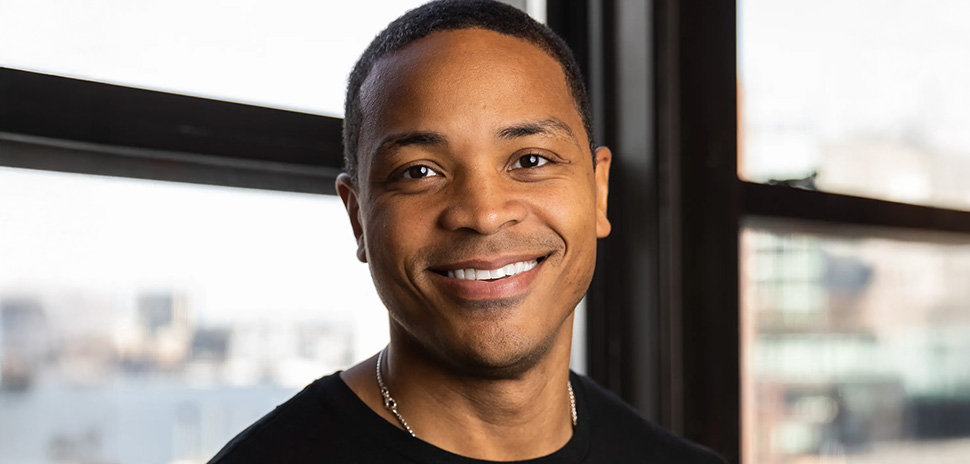

For Dr. Robert Rennaker, “It’s about the veterans.” As a veteran himself, he’s concerned with how much PTSD is affecting those who served.

“We sent these people to fight for us,” Dr. Rennaker said. “They came back, but they’re injured, and we need to help them; we need to undo the PTSD caused by their service to our country.”

In general, there is a belief that PTSD stems from a chemical imbalance in the brain, but that is not the case. The violence on the battlefield can cause the brain to rewire. Just like the rewiring of the brain that causes PTSD can be created, it can also be undone. The memories are not erased, but the connections to the emotional part of the brain are disconnected.

This change allows people to adjust to daily and to those trauma memories. This same approach is not only helpful for veterans but is also valuable for someone who might have experienced a violent or traumatic event such as sexual assault.

For the TxBDC team, the hope is that this technology can reduce or even eliminate PTSD. The team has seen some promising results from the first study. Of the seven subjects that completed the study, none of them were diagnosed with PTSD following the therapy, and the PTSD had not returned at six months post-therapy. The rewiring has allowed them to connect with others, resume working, and live fuller active lives.

Implanting a small chip on the vagus nerve only takes forty minutes in an outpatient procedure. The chip stimulates the vagus nerve to release the chemicals in the brain that enhance learning. During prolonged exposure therapy, the patient is in a safe and comfortable office with a trained therapist. The patients recount their trauma memories in twelve one-hour sessions. The vagus nerve is stimulated during these sessions.

Over time, the brain learns that those memories are no longer a threat. Patients can also deliver the therapy in the comfort of their own homes by listening to the memories recorded on a tablet that can activate the chip on the vagus nerve.

Making bench to market a reality

Dr. Robert Rennaker, Texas Instruments Distinguished Chair in Bioengineering, Professor of Neuroscience at UT Dallas

While the initial trial has proven very successful, more extensive research is needed to bring this life-changing treatment to those who would most benefit. The research is costly, and funding is required to ensure the team can continue with the next crucial round of testing. Future possibilities for this research extend beyond PTSD to conditions such as depression, stroke, spinal cord injury, and pain.

For Dr. Rennaker, the mission is personal.

“Life is short. When I leave here, I want to have improved people’s lives,” he said. “I want to have made this world a little bit better, especially for those that bear the visible and invisible scars that resulted from the defending of our country.”

Learn more about TxBDC’s breakthrough technologies

In addition to pioneering neuroplasticity-based treatments for PTSD and spinal cord injury (SCI), TxBDC researchers are advancing therapies for tinnitus, traumatic brain injury, and peripheral nerve injury—along with an FDA-approved stroke treatment.

Interested in a clinical trial? As of this publication, TxBDC is accepting applicants for PTSD, stroke, and spinal cord injury (SCI) trials. Contact TxBDC to learn more.

For collaboration opportunities, funding support, or additional information, email the research team.

Story by Alyssa Galganov, Office of Research and Innovation, The University of Texas at Dallas.

Don’t miss what’s next. Subscribe to Dallas Innovates.

Track Dallas-Fort Worth’s business and innovation landscape with our curated news in your inbox Tuesday-Thursday.